Bank funding: evolution, stability and the role of foreign offices

There are four key findings. First, the mix of local banking systems' funding sources has been shifting in recent years, from cross-border to local and, within cross-border, from inter-office (ie from related banks) to unrelated sources. Second, this shift has implications for funding stability, as local funding is typically more stable, but unrelated cross-border funding is more sensitive to international shocks than is inter-office funding. In particular, we show that inter-office funding was the more resilient part of cross-border funding during the GFC and in the face of fluctuations in global financial conditions. Third, the shift in funding mix over the past five years is driven primarily by a relative retreat of FBOs, which rely more than DBOs do on funding from cross-border sources. This is consistent with a generalised retreat from global banking business models, as banking groups have started operating more out of their home offices rather than via their foreign affiliates. Fourth, the retreat of individual foreign offices drives an increasing concentration of FBO nationalities in local banking systems, which has historically been connected with more volatility in cross-border funding.

This article builds on two strands of international banking research. The first is the literature on the stability of foreign bank funding and lending (eg Claessens and van Horen (2013), McGuire and von Peter (2016)). We contribute to it by highlighting the importance of inter-office flows for cross-border funding stability and studying sensitivities to global shocks across cross-border funding sources. The second is the literature on banks' international business models (eg Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012), CGFS (2010), McCauley et al (2010)). We bring aspects of these studies up to date by showing how the funding profiles and the relative size of FBOs and DBOs have evolved in recent years.

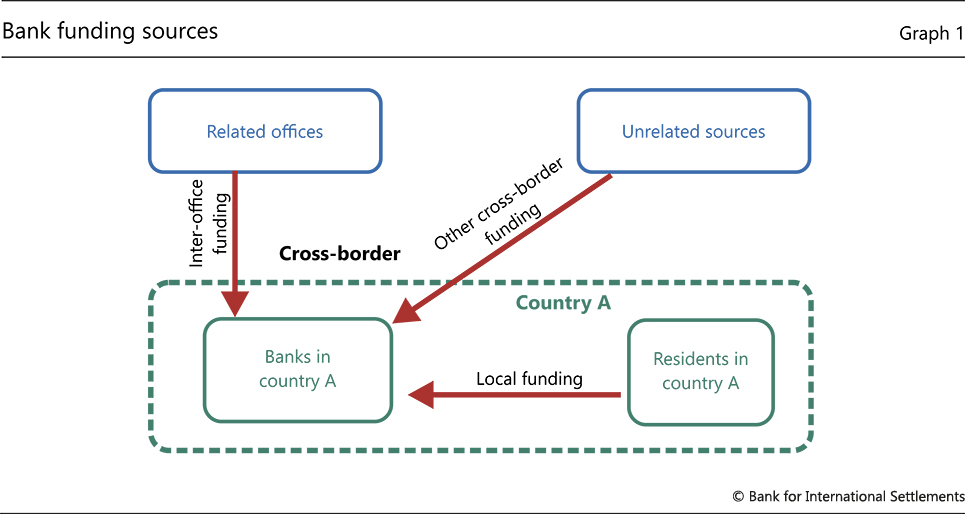

Graph 1

Close all

The rest of the article is organised as follows. The first section documents changes to banks' funding mix and sets out the implications for funding stability. The second section looks under the hood, showing that these trends are driven by the evolution of FBOs and DBOs and their differences in terms of funding models. The third section documents an increase in FBO nationality concentration, which also has implications for funding stability. The final section concludes.

Funding sources: recent shifts and relative stability

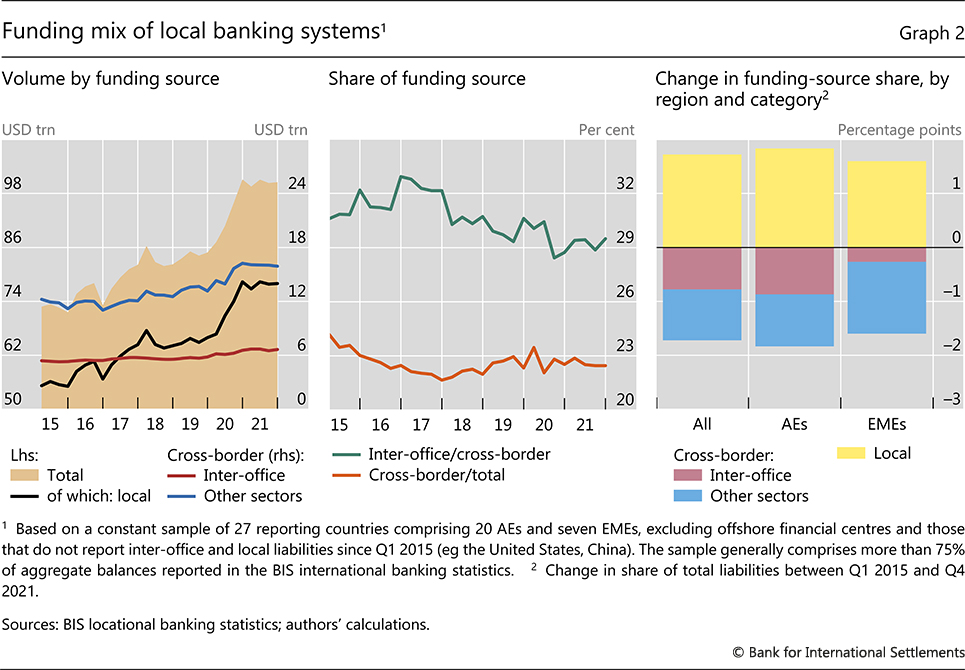

The mix of funding sources for local banking systems has been shifting in recent years. Following a post-GFC retrenchment, total liabilities grew by 39%, from $70 trillion in Q1 2015 to $101 trillion3 in Q4 2021 (Graph 2, left-hand panel). However, the share of funds obtained from cross-border sources showed some decline, falling from 24% to 22% over the same period (centre panel). Within the cross-border segment, funding shifted away from inter-office, falling from 31% of cross-border liabilities to 29%. Overall, local banking systems have replaced cross-border funds, especially inter-office funds for banks in advanced economies (AEs), with local funding (right-hand panel). While these shifts seem small in percentage terms, the decline in the cross-border funding share represents a $1.7 trillion reallocation of the global aggregate.

Graph 2

Close all

Previous research points to a stability hierarchy among funding sources, particularly in the face of international shocks. Most stable is local funding, especially deposits (Ongena et al (2015)). Within cross-border funding, inter-office funding has been shown to be the most stable (Reinhardt and Riddiough (2015)), probably as a result of the pursuit of banking group-wide objectives (De Haas and Van Lelyveld (2010)). Cross-border funding from unaffiliated sources is generally the least stable.

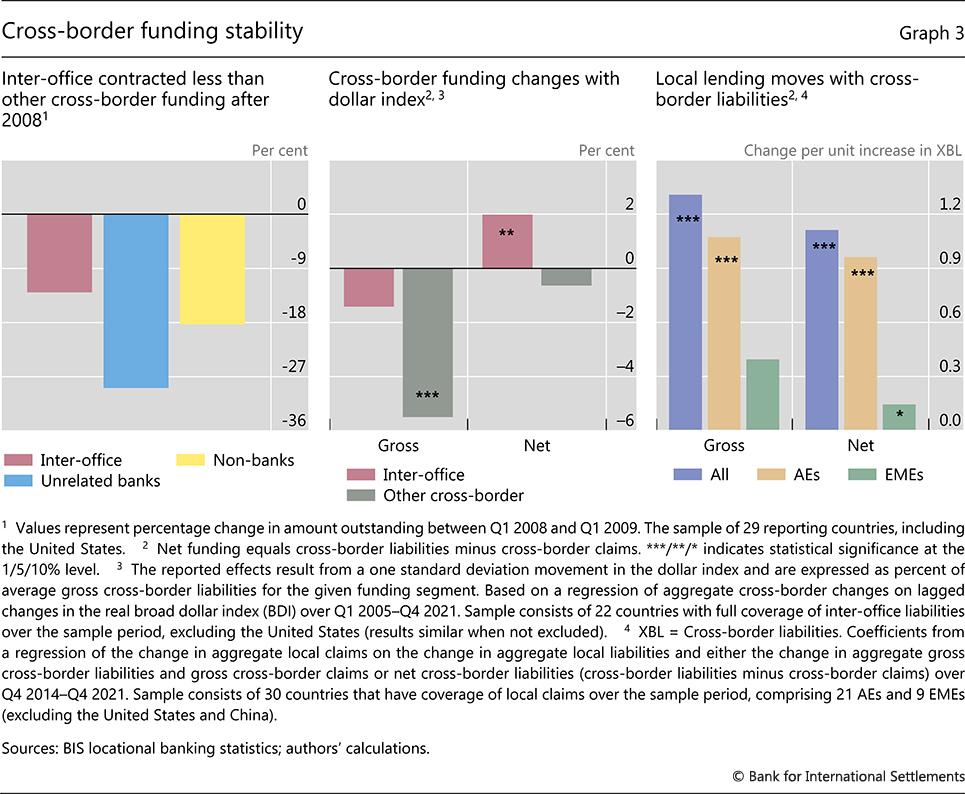

Consistent with these stylised facts, we find that inter-office funding was the most stable part of banks' cross-border funding during the GFC. Overall, cross-border funding plunged from its peak in Q1 2008 through Q1 2009, but inter-office cross-border liabilities declined by only 13% in aggregate, while liabilities sourced from unrelated banks and non-banks, declined by 29% and 18% respectively (Graph 3, left-hand panel).

Graph 3

Close all

In line with previous studies, we also find that inter-office funding is less sensitive to global financing conditions, as proxied by the broad dollar index (Graph 3, centre panel).7 For a one standard deviation change in the dollar index (a roughly 8% appreciation), cross-border liabilities fall by less than 1.5% for inter-office but by 5.5% for other sources (for an overall decline of around 4%). Net changes (whereby cross-border claims are subtracted from liabilities) suggest that inter-office sources actually compensate for the retrenchment of unrelated entities.

Swings in a local banking system's cross-border funding go hand in hand with similar swings in domestic lending. We obtain this result from an empirical analysis, that considers both gross and net cross-border liabilities. In particular, we find that, when such liabilities decline, so do local claims, by an equal amount for AEs and by 40% of the gross cross-border liability decline for emerging markets (EMEs) (Graph 3, right-hand panel).

Underlying foreign and domestic banking office trends

The shifts in global funding mix indicated above reflect the confluence of three factors: the declining share of foreign banking offices (FBOs) relative to domestic banking offices (DBOs); the differences between the FBO and DBO funding models; and changes in liability structures within these groups, particularly among DBOs. We discuss these factors in turn.

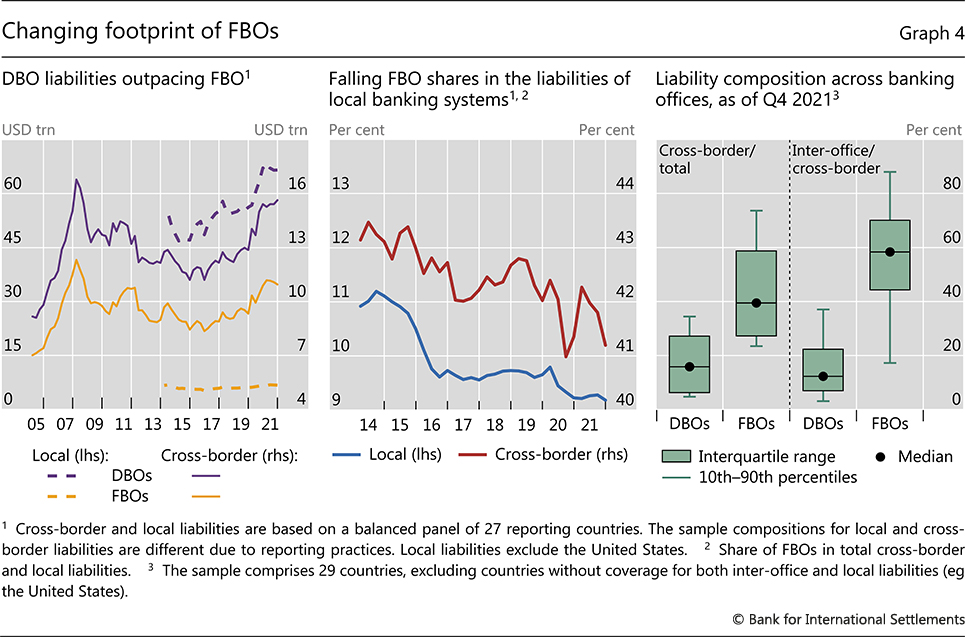

Graph 4

Close all

Following the post-GFC retrenchment in international banking, FBOs' liabilities grew from around 2016, but by less than those of DBOs did (Graph 4, left-hand panel). As a result, FBOs' share in local banking system liabilities declined, from 43% in Q1 2015 to 41% in Q4 2021 for those sourced cross-border. In the case of local liabilities, the corresponding decline was from 11% to 9% for local liabilities (centre panel).

FBOs' funding models differ from those of DBOs in several respects. Cross-border positions account for a far higher proportion of FBOs' balance sheets, reflecting these offices' generally greater international focus (Graph 4, right-hand panel).8 In addition, FBOs are nodes in global banks' international intermediation networks, and part of their function is to help manage flows of liquidity within global banks. This naturally generates a higher proportion of inter-office positions. FBOs also utilise much more US dollar funding (Box A). These differences across FBOs and DBOs would affect the funding structure of local banking systems, as the share of FBOs declines.

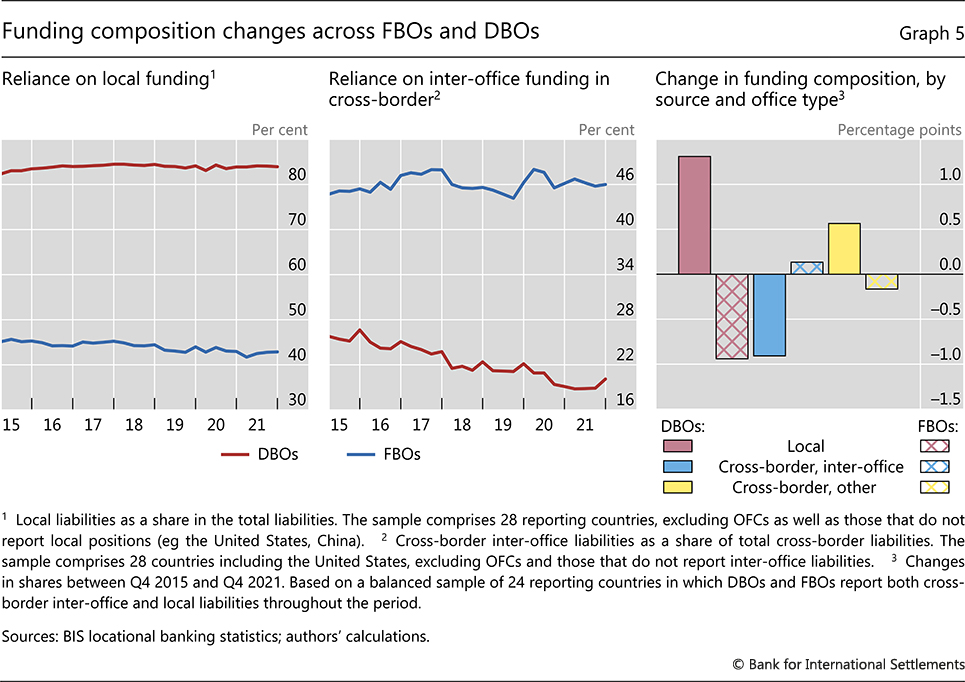

Within the aggregate FBO and DBO groups, the funding mix has been mostly stable over the past five years, with a few notable shifts. For both FBOs and DBOs, the share of funding from local sources remained largely unchanged between Q1 2015 and Q4 2021 (Graph 5, left-hand panel). However, DBOs have reduced the use of inter-office sources, from 26% to 20% of cross-border liabilities over the same period (centre panel).

Graph 5

Close all

In sum, the decline in FBOs' liabilities relative to those of DBOs, the differences in these offices' funding structure, and changes in the funding mix within each group have delivered the following shift at the level of local banking systems: from cross-border inter-office to other cross-border and local funding. (Graph 5, right-hand panel). The underlying reshuffling of DBO funding sources is consistent with the generalised retreat of global banking: banking groups have reduced the role of their foreign affiliates to do more business directly from their home offices.

The impact of a shift away from FBOs on funding stability is a priori unclear. Granted, there is evidence that foreign banks tend to be more vulnerable to international shocks than domestic banks are (McGuire and von Peter (2016)). However, such stylised facts reflect foreign banks' greater use of non-deposit funding, especially cross-border funding, whereas FBOs and DBOs that fund themselves similarly are similarly stable.9 In addition, FBOs tend to have more stable cross-border funding because their parents support them in times of stress, probably as part of an overall optimisation for the banking group (Eguren-Martin et al (2022), De Haas and Van Lelyveld (2006, 2010), Barba-Navaretti et al (2010)). A decline in FBOs' share of the local banking system's cross-border liabilities reduces the reach of these inter-office networks. In the light of the discussion in the previous section, this could impair local banking systems' funding stability, all else equal.

First, please LoginComment After ~