Pressure builds on Bank of England for hefty interest rate rise

Another rise in UK interest rates was already on the cards before Queen Elizabeth’s death delayed the Bank of England’s decision. If anything, the pause has made the case for rapid monetary tightening even clearer — the only question is how far policymakers will go at their meeting on Thursday.

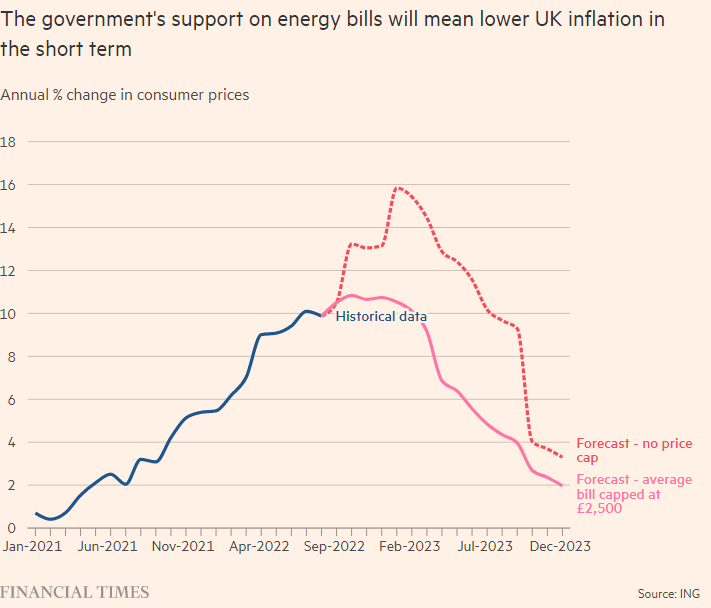

The big change since the BoE Monetary Policy Committee last met in early August has been new prime minister Liz Truss’s plan to cap energy bills for households and companies, at an estimated cost of £150bn. This will lead inflation to fall faster in the next few months, but the plan amounts to a huge fiscal stimulus that will probably keep it higher in the medium term, unless the MPC acts to offset it.

“We do have work to do,” BoE chief economist Huw Pill told MPs after Truss’s energy measures were announced, adding that the MPC’s focus would be on how they affected inflation “at longer horizons”.

Financial traders are betting the MPC will act even more aggressively in response to high inflation this week than it did in August, when interest rates were raised by 0.5 percentage points to 1.75 per cent — the sharpest increase in 27 years. Now, market pricing implies a bigger, 0.75 percentage point rise, with rates peaking at 4.5 per cent next year.

The MPC’s members, however, are likely to split on the scale of monetary tightening. With the UK economy hovering on the brink of recession, at least one member, Silvana Tenreyro, has taken a more dovish line, and could vote for a 0.25 percentage point rise, while others are likely to favour a second successive 0.5 percentage point increase. Analysts said it was unclear what the majority of MPC members will decide.

One argument for the BoE to go big is that it risks looking irresolute compared with its peers. The European Central Bank raised interest rates by 0.75 percentage points this month for the first time since the euro’s launch. Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve looks likely to deliver a third consecutive 0.75 percentage point increase on the eve of the MPC’s decision. If the BoE is seen as a laggard, it could worsen the sell-off in sterling — which hit a 37-year low against the dollar on Friday — adding to inflationary pressures.

“The MPC is boxed into a corner right now and must raise bank rate quickly to prevent sterling from depreciating further, and to signal to households that it is serious about tackling inflation,” said Samuel Tombs, at the consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, who nonetheless argued the outlook for inflation was improving and that policymakers did not need to “strangle the economy” with a sustained series of big rate increases.

Other analysts believe that inflationary pressures are still building in the UK economy, with data released over the past week showing that stagnant output and falling retail sales have not stopped service prices rising, or nominal wage growth accelerating in a buoyant labour market. “If persistent surprises in the wage and price data since August, hawkish developed market central banks, a weaker currency, a gilt market sell-off and . . . fiscal easing don’t push the MPC to up its tightening pace to 75 basis points . . . it’s hard to see what would,” said Allan Monks, economist at JPMorgan.

Policymakers will also be worried by dwindling public confidence in the BoE’s response to surging inflation. Although UK consumer price inflation dipped a little to 9.9 per cent in August on the back of lower petrol prices, it remains the highest in the G7. The MPC “needs to be bolder to restore its credibility”, said Julian Jessop, fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think-tank, arguing that a 0.75 percentage point increase “would send a stronger signal that the bank is serious about getting inflation back down over the medium term”.

Others, however, think policymakers will be more cautious and content themselves with a 0.5 percentage point rise for now. Although the new direction of government fiscal policy is clear, the MPC will be meeting before chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng outlines on Friday details of Truss’s proposed tax cuts and the Treasury’s costings of the energy support package, and policymakers will only be able to incorporate these into their forecasts in November.

Fabrice Montagné, economist at Barclays, said a sudden turn for the worse in business sentiment showed that the economic slowdown was broadening, and that this “should make the arguments of the most dovish [MPC] members more palatable”.

A further question is whether the MPC will still press ahead with plans to start reducing the stock of assets it amassed under quantitative easing programmes, as it had signalled in August — given the possibility of the government launching big bond sales as it relaxes its fiscal stance.

Whatever the MPC decides on Thursday, many analysts think it will need to keep raising interest rates for longer than looked likely in August, as a result of developments in energy markets and the government’s fiscal stimu

s.

“Even if the bank doesn’t hike as far as markets expect, we do think the arrival of government stimulus means the BoE won’t be racing towards rate cuts next year, unlike some of its developed market counterparts,” said James Smith, economist at ING.

“Liz Truss’s policy will probably make the bank more likely to hike rates faster and further,” said Paul Dales, at the consultancy Capital Economics, which now expects interest rates to rise to 4 per cent.

First, please LoginComment After ~