Financing a Net-Zero Middle East

Since the 2015 adoption of the Paris Agreement, the Middle East has significantly accelerated its climate change commitments and initiatives. Several Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have set national net-zero targets, and many major private-sector companies have published decarbonization goals of their own.

The region is facing up to the dire threats of climate change and building a foundation for decarbonization. It is making the political, social, and financial commitments that will be required. Yet despite such substantial progress, the journey toward net zero will be long, difficult, and costly.

The key players in the region, in particular regulators and development banks, can have a central role in unlocking and overseeing the capital required to fund the transition. Traditional financial institutions also need to participate in financing the path to net zero.

Ultimately, all of these entities should accelerate their preparation for a long-term green transition—one that can present opportunities, which, over time, can benefit their organizations as well as the entire region.

The Lay of the Land

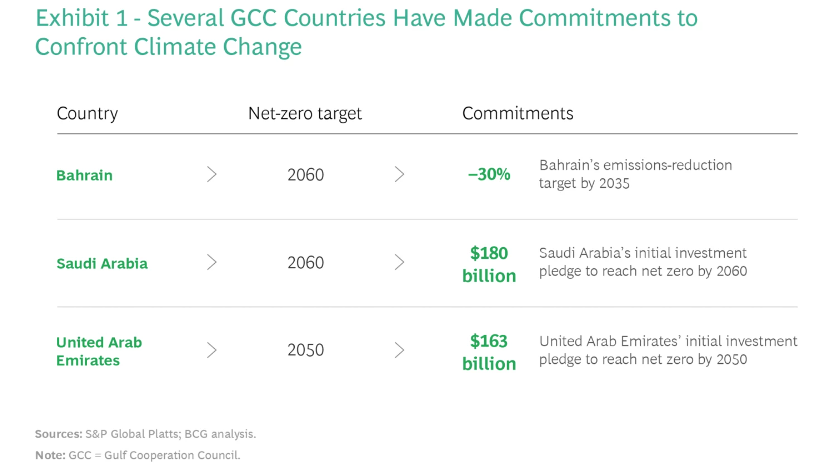

Of the six GCC countries, three—Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—have made clear decarbonization commitments. (See Exhibit 1.) But the sheer amount of investment that these countries need to facilitate a transition to green energy and achieve national net-zero goals is enormous. The UAE, for example, has already committed $163 billion to its net-zero pledges, but an independent analysis by Standard Chartered estimates that the total investment needed is $680 billion, leaving a gap of more than $500 billion.

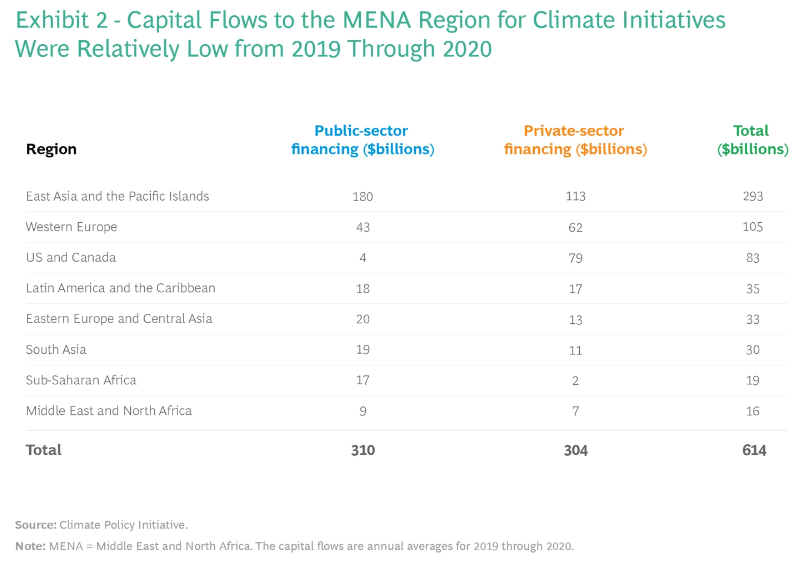

Other GCC and Middle Eastern countries, as well as Africa, are likely to face a similar challenge. Indeed, according to the Climate Policy Initiative, capital flows to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region to fund climate change initiatives have been among the lowest to any major global region in recent years. (See Exhibit 2.)

Filling the gap, and moving forward effectively, will require the cooperation of regulators, development banks, and traditional financial institutions.

The Important Role of Regulators

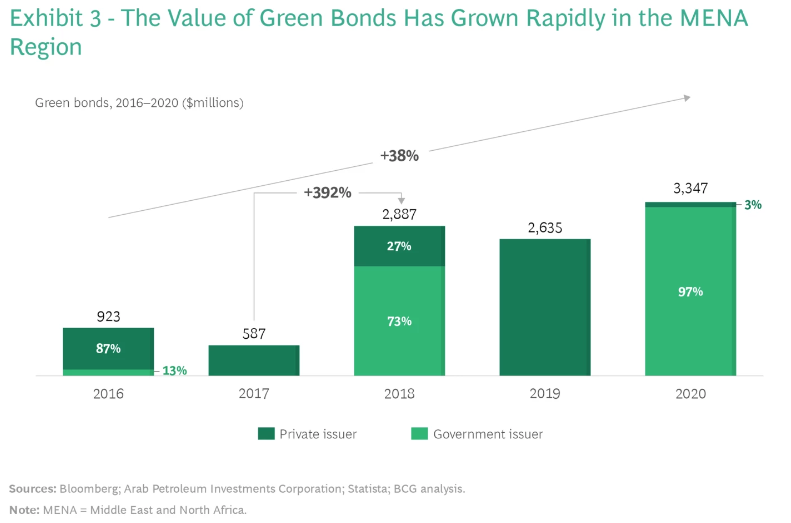

The value of green bonds that have been issued by Middle Eastern countries has shown appreciable growth in recent years. (See Exhibit 3.) Yet the green bond market must greatly expand to truly move the needle toward net-zero goals. Financial regulators can incentivize that growth in several ways.

Greening the Financial System. To attract more investment in green energy projects, the European Union (EU) and several regions are gradually greening their financial systems. The governments are adopting policies and regulations that encourage financial institutions to redirect capital toward sustainable investments and away from projects that do not sufficiently support decarbonization targets. The US Securities and Exchange Commission is also considering regulations that would drive greater transparency on how companies integrate climate-related risks and opportunities into their business decisions. Policymaking and regulatory intervention are key starting points, and financial regulators in the Middle East are poised to play a leading role in putting the region on track.

Devising Standards for Climate Reporting and Disclosure. Among the important regulatory interventions is setting and enforcing standards for climate reporting and disclosure, as well as creating taxonomies of sustainable activities. The Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) is a leading forum for coordinating these efforts and exchanging best practices among regulators. NGFS members have expressed their support for recommendations made by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, with some members already incorporating initiatives into their regulatory frameworks. Several of the Middle East’s financial regulators have joined the NGFS, including the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Abu Dhabi, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, the Financial Regulatory Authority for Egypt, and the central banks of Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon.

Creating a Carbon-Pricing Framework. Another potential regulatory intervention is to create a carbon-pricing framework that stimulates demand for investments in renewable energy and low-carbon technologies. Currently, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are not priced into regional markets, which reduces the incentive to cut emissions. Consequently, low-carbon technologies are not competing on an even playing field with legacy—and frequently subsidized—high-carbon activities.

Regulators and policymakers can motivate high emitters to make changes by establishing carbon prices that adequately represent the cost of GHG emissions and that reflect international carbon price levels. Such pricing could not only incentivize investments in clean technology but also reduce subsidies for high-carbon projects, making cleaner projects more economically attractive. Regulators and policymakers could also create other incentives to support decarbonization and develop environmental and industrial policies that support climate objectives.

Establishing Carbon Markets. Carbon credit markets offer another opportunity for regulators to facilitate the green transition. Enforcing mandatory carbon caps and creating compliance markets would likely create demand for carbon credits. The EU Emissions Trading System and California’s Compliance Offsets Program offer examples of such initiatives.

Voluntary carbon markets present a further opportunity, although care must be taken to ensure that such markets result in actual decarbonization. For example, the Abu Dhabi Global Market, one of the UAE’s international financial centers, is working on a framework for the first-ever regulated voluntary carbon market. (See “Developing a Sustainable Finance Ecosystem.”)

Development Banks Are Critical Players

In these relatively early stages of financing the green transition, there is a significant need for investors. Development banks have a vital role to play, a mandate they can carry out through three core activities:

- ♦Providing financing for green projects that have lower risk-adjusted returns or higher investment risks; such projects include those that are researching and developing innovative technologies used for renewable power and carbon capture usage and storage, particularly in industries such as steel and shipping

-

- ♦Mobilizing private capital to invest in green projects by improving their risk-adjusted returns with various risk-mitigation instruments

-

- ♦Using internal expertise to provide support and advice to policymakers and regulators about the reforms needed to scale up financing for their climate and development priorities

The deployment of public capital—in combination with private funding and the development of innovative risk-sharing structures—can also provide development banks with an opportunity to fulfill their climate mandates.

Traditional Financial Institutions Are Key Enablers

Regulatory pressure in most MENA countries is not yet strong enough to compel regional banks to take immediate action on climate issues, but incumbents should consider it for several reasons.

Climate change poses an array of risks to banks’ portfolios. In particular, larger banks in countries that export fossil fuels typically have high exposures to the oil and gas industry and to other high-emitting sectors of the economy, such as transportation, construction and infrastructure, and shipping. Such exposure results in significant transition risks for those banks associated with decarbonization—risks that are in addition to the physical risks to their assets that directly result from climate change.

Regional banks also have an opportunity to benefit significantly from financing the transition of the oil and gas industry and other strategically important sectors to cleaner, more sustainable technologies. As noted, the value of green bonds has been growing rapidly in the Middle East. According to Gulf News, in 2021, the total issuance of green and sustainability-linked debt in the region reached $18.7 billion, more than a fourfold increase over $4.5 billion in 2020.

In addition, banks with a larger share of international equity or debt investors may be increasingly questioned by stakeholders about their emissions footprint (which includes the emissions of the companies they are financing) and their strategy to reduce it. In essence, banks can benefit from setting emissions-reduction targets for themselves and from building the capabilities needed to understand the transition pathways of their clients.

To effectively demonstrate their commitment to climate action and potentially influence the global push toward net zero, regional banks should participate in key alliances—such as the Net-Zero Banking Alliance and the Science-Based Targets initiative—as well as join working groups such as the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials.

As the decarbonization drive accelerates, the role of capital as the enabler of the green transition is becoming more obvious and more urgent. A robust regulatory framework is crucial to future-proofing the region’s financial industry and allowing it to benefit from the green transition. Combining this foundation with support from development banks can become a winning formula in laying the financial groundwork for reaching regional net-zero goals in a timely manner. Moreover, the Middle East’s experience could serve as a model for other regions and countries seeking financial solutions for their own decarbonization efforts.

This article was developed jointly and cooperatively by BCG and ADGM.

First, please LoginComment After ~