"Three New Drivers of Asset Markets"

I am happy to join you at this annual conference in-person this year. Congratulations Jenny on your appointment as Chair of IMAS. IMAS has been working closely with MAS, to grow green finance, develop talent, and digitalise the asset management industry. We look forward to further strengthening this productive partnership.

The investment business has never been more interesting – if by interesting we mean dealing with new uncertainties and unknowns. Let me highlight three key uncertainties that will drive financial market returns and risks:

- over the short term: inflation

- over the medium term: geo-economic fragmentation

- over the long term: climate change

SHORT-TERM: INFLATION

In the short run, the key driver of risk and return is the trajectory of interest rates – which in turn depends on the inflation outlook and monetary policy response.

The good news is that inflation seems to have peaked and come off a bit. The bad news is that it is still quite high. [1]

- Global headline inflation appears to have peaked, averaging 5.6% in Q4 2022 compared to 6.0% in Q3. This has taken place in line with the sharp fall in food, energy, and logistical costs.

- But inflation remains well above the average of 2.5% seen in the decade before COVID-19 (2010-19).

- Moreover, global core inflation rose from 3.8% in Q3 2022 to 4.1% in Q4.

With headline inflation coming off its peak, most central banks have shifted to a more moderate pace of tightening. But with inflation still well above targets, the tightening cycle has some ways to go.

- The US Fed, European Central Bank (ECB), and Bank of England have stepped down to a more modest range of 25 to 50 basis point rate hikes this year compared to the successive 50 to 75 basis point hikes last year.

- But expectations by some market participants that the tightening cycle will end soon and that central banks may even start easing are excessively optimistic.

- Forward guidance by advanced economy central banks indicates further tightening to cool inflation. Both the US Fed and the ECB have reiterated their commitment to achieve their inflation targets of 2%.

The key challenge facing most central banks is to secure a return to low inflation without incurring too large a cost to growth or financial stability.

- Thus far, the disinflation process has taken place in an orderly manner, without dislocations to the functioning of the global economy and financial markets.

- But continuing to get this balance right will be a challenge, especially if inflation gets stuck at too high a level.

- There are complex spillover effects from synchronised policy tightening across countries. These effects could help dampen inflation domestically to the extent they reduce imported inflation. But they could also exacerbate inflation if the domestic exchange rate weakens.

- Adding to the complexity is that monetary policy operates with long lags. If policy is tightened at a pace that does not take into account the effects of previous hikes, we risk a deeper economic downturn or financial stresses.

- But if policy tightening ends prematurely, we risk destabilising price expectations, entrenching inflationary pressures, and eroding central bank credibility.

Of course, the question of how fast core inflation can return to central banks’ target bands is contingent not just on monetary policy.

The speed of disinflation is subject to three near-term uncertainties: labour market dynamics, China’s re-opening, and a surge in food and energy prices.

The first uncertainty is labour markets: continued labour market tightness could lead to persistent services inflation, especially in the advanced economies.

- COVID-19 presented the ultimate supply shock for labour markets across the world, as workers exited the labour force in large numbers.

- Even with the return of most workers post-pandemic, sectoral labour shortages remain severe in many countries, especially in contact-intensive industries such as retail trade, food, hospitality, and manufacturing.

- With labour markets persistently tight in most advanced economies, nominal wage growth has been robust.

There are three possibly structural factors driving tight labour markets and wage pressures.

- First, workers have been moving away from low-wage services jobs and moving up the occupational ladder, generating worker shortages in these services jobs. [2]

- Second, there has been a significant fall in the number of immigrant or foreign-born workers in the advanced economies, particularly among lower-wage occupations. [3]

- Third, preferences for work relative to non-work activities may have shifted during the pandemic. Recent US data show a persistent decline in desired hours worked especially among better-educated workers. [4]

- It remains to be seen whether these labour supply shifts are irreversible.

Ultimately, so long as labour shortages continue, prices will edge higher compounding the pressure on central banks to hike further later this year.

The second uncertainty is posed by China’s re-opening: a stronger-than-expected infrastructure-led rebound in China could pose an upward risk to global inflation. While we can anticipate an uptick in demand from China’s reopening, the extent to which this imparts a renewed impulse to global inflation is unclear.

For now, China’s near-term developments appear unlikely to decisively reverse the global disinflation trend in 2023.

- The recovery of China’s consumer demand is expected to be led by domestically oriented consumer services rather than tradable goods.

- Unlike in advanced economies, China has a substantial supply of deployable labour suggesting that significant labour market tightening is unlikely.

- Producer prices in China are continuing to decline. The easing of pandemic-related supply chain disruptions will help moderate producer price pressures, imparting a mildly disinflationary impact on the global economy.

However, a sharp rebound in economic activity in China on the back of robust infrastructure spending and an accelerated recovery of the property market could lead to higher global commodity prices.

- A jump in import demand for construction materials threatens to rekindle inflationary pressures on global commodities, reversing the current downtrend that began last year.

- Heightened commodities prices will add to higher input costs for global manufacturers, whose margins are already under pressure from elevated wages. If manufacturers pass on these higher production costs, we could see an increase in goods price inflation.

At a time when services inflation is proving stubborn, a resurgence in goods prices will negate the hard-fought gains in the nascent disinflation process.

The third uncertainty is fresh shocks to food and energy prices.

- Lower global food and energy prices have largely facilitated the fall in global headline inflation so far.

- But the nascent disinflationary trend may be interrupted by a rise in food and energy prices. For instance, in January this year, firm food and energy prices elicited stronger-than-expected inflation outturns.

Upside shocks to food and energy prices can emanate from a few sources.

- Unfavourable weather conditions could dampen agricultural yields. This happened in Asia in January.

- The fall in OPEC oil output remains a factor underpinning some firmness in oil and gasoline prices.

- An escalation in geopolitical tensions could contribute to bouts of volatility in commodity prices.

So, what does all this mean for financial markets?

Financial markets may take a while to adjust to this new regime of higher interest rates, and that adjustment may not be smooth.

- We witnessed last year how such a disorderly adjustment could unfold, when central banks raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace.

- When interest rates rise rapidly, future cashflows will be discounted at a faster rate than the current cashflows can grow. As a result, most financial assets, which represent a stream of future cashflows, will do badly.

Last year, the financial markets performed poorly even though there was no economic or financial crisis.

- Global equities and bonds fell by between 16% and 20%. A traditional 60/40 investor would have lost 18% in portfolio value in 2022 alone.

- This is in stark contrast to the preceding 30 years, where such a portfolio would have earned a respectable 8.7% per annum.

- In fact, last year, it did not matter if you were 60/40 or any other combination. So long as your portfolio was exposed to global stocks and bonds, the portfolio would likely have performed negatively in 2022.

Against this backdrop, investors will need to consider building greater resilience in their portfolios.

- What should be the appropriate composition of the portfolios?

- How will each asset class perform under different growth and inflation environments?

- What is the appropriate allocation to inflation-protection assets, such as real assets, inflation-linked bonds, and commodities?

- What should be the exposure to energy given the opposing pulls of short-term inflation dynamics and longer-term climate risks?

- Is there a role for tail-risk hedges such as gold and how large should that role be?

MEDIUM TERM: GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION

All said and done, inflation will eventually come down and interest rates normalise, though both are likely to be slightly higher than what we have been used to.

Over the medium term, the key driver of returns and risks in the financial markets will be geoeconomic fragmentation.

Rising tensions between US and China have led to higher trade barriers, tighter cross-border investment restrictions, and greater domestic production of critical goods deemed to be of strategic importance.

- On the trade front, slightly more than 60% of the trade between the two countries is subject to tariffs from one side or the other.

- Investment flows between the US and China have slowed amid tighter regulations by the US to safeguard national security and supply chains.

- Both countries have stepped up domestic industrial policies.

- China has committed US$1.4 trillion over five years to augment domestic technology and digital infrastructure.

- The US has passed the US$280 billion CHIPS Act to boost semiconductor research and production capabilities over the next ten years.

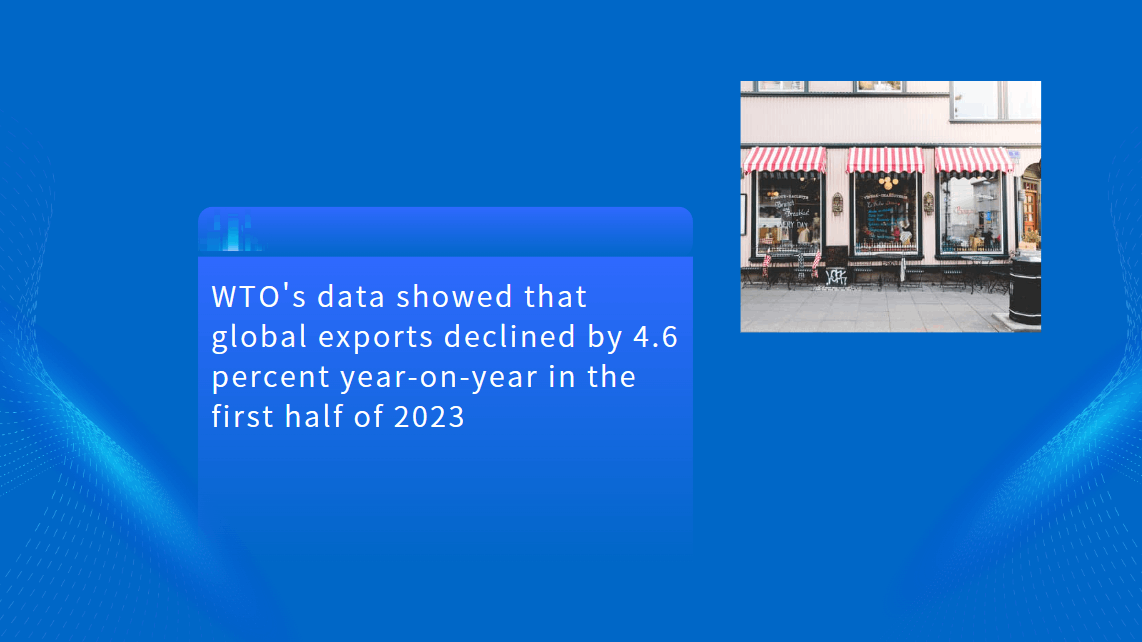

These measures have led to not just reduced trade and investment between the two countries but is also shaping broader shifts in global trade patterns and supply chains.

These shifts are most evident in the electronics industry.

- America’s share in China’s electronic exports fell by 4% points between 2017 and 2021, while regional economies such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and Thailand gained market shares.

- At the same time, these three economies exported more to the US market in 2021, compared to 2017. Vietnam has seen the largest increase in its exposure to the US market, at 14% points.

- Looking ahead, increased domestic capacity for electronics production in both China and the US will likely lead to a substitution of imports.

- The US-proposed Chip 4 alliance with Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan for semiconductor production could potentially divert trade flows away from countries that are not part of this arrangement.

- At the same time, it is also possible that some trade could be diverted from China to lower cost regions such as Vietnam, India and Mexico, which are emerging as competitive assembly locations for final electronics products.

The result of all this geoeconomic fragmentation is most likely slower global growth.

- Several studies show that the long-term effects of receding globalisation are costly.

- According to an IMF study, a scenario of limited trade fragmentation would reduce global GDP by 1.2%. [5]

- A WTO study found that under a more adverse scenario of a full technological decoupling from 2020 to 2040, the loss in GDP would be 8.0-12.0% in individual countries during this period. [6]

- Ultimately, low-income developing countries furthest from the technological frontier will suffer most acutely from reduced knowledge diffusion from advanced economies.

Supply chain diversification will increase inflationary pressures.

- First, relocating operations will incur high upfront costs. Even if governments have the fiscal resources to subsidise duplicate supply chains, there may be insufficient labour to sustain it.

- Second, restrained global competition will increase the market power of larger firms or domestic oligopolies, resulting in reduced innovation and higher prices.

- Third, reduced technology sharing and collaboration will hamper the widespread adoption of best practices, thereby reducing efficiency and increasing costs.

Fragmentation in the real economy will also have an impact on capital flows and financial markets.

- Geoeconomic fragmentation elevates financial market risk and disruption, as capital flows become more regionalised and less global. Consequently, this reduces market liquidity and returns and increases market volatility.

- The impact of disruptions in cross-border capital flows falls disproportionately on the less developed countries.

In short, no country will emerge unscathed with rising geoeconomic fragmentation, with emerging market economies set to bear the brunt of reduced trade and capital mobility.

- In the last decade, emerging market financial assets benefitted from the rising tide of capital inflows that created a virtuous cycle of capital market reforms, deeper liquidity, and vibrant market development, which in turn drew in more capital inflows.

- The impact of a slowdown in capital inflows would be felt most acutely in those countries with the least developed capital markets and rely the most on foreign capital, putting them at risk of financial or balance of payments crises.

- Emerging markets that have already reached a more advanced stage of development, included in global indices, and run healthy external balances may be more resilient.

LONG TERM: CLIMATE CHANGE

Perhaps the most significant financial risk for investors over the long term is climate change. This risk can materialise in two ways.

- First, physical risks from climate change itself – such as physical damage to properties and assets, disruption to supply chains, production stoppages, and reduced agricultural yields. They will reduce growth and push prices higher.

- Second, transition risks from government policies, technological advances, and shifts in demand patterns aimed at mitigating climate change and promoting sustainability.

- For example, the introduction of carbon pricing will change the earnings profiles of businesses, favouring firms and industries with cleaner technologies and lower carbon emissions relative to more carbon-intensive firms and industries.

The effects of climate change on the global economy and asset markets are hard to predict.

- First, there are inherent uncertainties in modelling climate outcomes and in assessing its impact on the global economy. This is due to the limited usefulness of historical data, potential non-linearities and tipping points in climate systems, and the long horizons over which climate change materialises.

- Second, there is uncertainty regarding technological developments and policy responses. The transition pathways that we take depend critically on how various green technologies advance and how cost-effective these technologies are. Climate policy is in turn contingent on these uncertain technological developments.

A key dimension that asset managers will need to build into their portfolios is climate resilience. They need to ask some searching questions.

- How will climate change affect the businesses that the portfolio is invested in?

- Which are the firms in the portfolio that have not made credible efforts to decarbonise their operations?

- What are the investments that run the risk of being stranded assets in a net-zero world?

- What are the investment opportunities as the world transitions to a low-carbon economy?

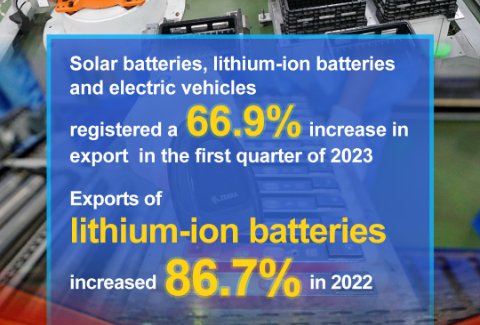

There have been significant policy moves on the sustainability front that will attract keen investor interest in the years to come.

- In US, the introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act will direct nearly $400 billion in federal funding to incentivise low-carbon investments – in areas such as clean energy generation and storage, electric vehicle manufacturing, and carbon capture.

- In Europe, the REPowerEU Plan will mobilise up to €300 billion of investment in areas such as renewable energy, storage and energy efficiency, to achieve the 2030 target of a renewables share of 45% in energy production.

There are also significant opportunities for sustainable investing in Asia.

- According to McKinsey’s estimates, net zero by 2050 would require about US$9.2 trillion of investment per year. Out of which, around one-third or US$3.1 trillion would be in the Asia Pacific.

Southeast Asia has high potential for climate action.

- Estimates from Bain shows that five sectors - renewable energy, electric vehicles, forest conservation, built environment and sustainable farming - account for 60% of Southeast Asia’s carbon abatement potential [7] .

- For example, renewables such as solar and wind will reach an annual US$30 billion opportunity by 2030, while electric mobility will be an annual US$50 billion opportunity by the same period.

To meet these needs, we need to catalyse blended financing.

- Many green and transition projects in emerging markets pose risks that are not commensurate with their expected returns.

- We need catalytic or concessional capital from multilateral banks, public and philanthropic sources to improve project bankability and crowd in private sector capital.

We need to strengthen the financial ecosystem to deploy blended finance at scale.

- This involves looking beyond the financing of individual projects and moving to a portfolio approach whereby concentration risks can be reduced through a diversified pool of assets.

- For instance, via multi-asset funds which invest in small scale renewable energy projects in specific markets.

- Securitisation can also mobilise private institutional capital, by allowing capital to be recycled from holding typically illiquid green and transition assets.

CONCLUSION

In sum, the operating environment for asset managers has become profoundly different from the last two decades, with inflation, geo-economic fragmentation, and climate change emerging as key drivers of financial markets. I hope today’s conference will give you insights on how to manage the risks and seize the opportunities ahead. Thank you.

***

- [1] The global inflation figures cited in this sub-para are based on the PPP-based weighted average of Singapore’s top 14 trading partners.

- [2] Forsythe, E, Kahn, L B, Lange, F and Wiczer, D (2022), “Where have all the workers gone? Recalls, retirements and reallocation in the COVID recovery”, Labour Economics, vol. 78, pp. 1 – 15.

- [3] Peri G and Ziour R (2022), “Changes in International and Internal Native Mobility after Covid-19 in the US”, NBER Working Paper, 30811.

- [4] Faberman, R J, Mueller A I and Sahin, A (2022), “Has the Willingness to Work Fallen during the Covid Pandemic?”, NBER Working Paper, 29784.

- [5] IMF (2023), “Staff Discussion Notes: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism”, The International Monetary Fund, January 15.

- [6] Goes, Carlos., and Eddy Bekkers (2022), “The Impact of Geopolitical Conflicts on Trade, Growth, and Innovation”, World Trade Organisation, July 4.

- [7] Source: Bain and Temasek, with contributions from Microsoft, Southeast Asia’s Green Economy 2022 Report: Investing behind new realities

First, please LoginComment After ~