Central Asian Dispute Resolution: Uzbekistan's New Arbitration Centre

One of only two double‑landlocked [1] countries in the world, thus lacking any direct ocean access, Uzbekistan is also the most populous country in Central Asia, accounting for 45% of the total population in Central Asia in 2023.

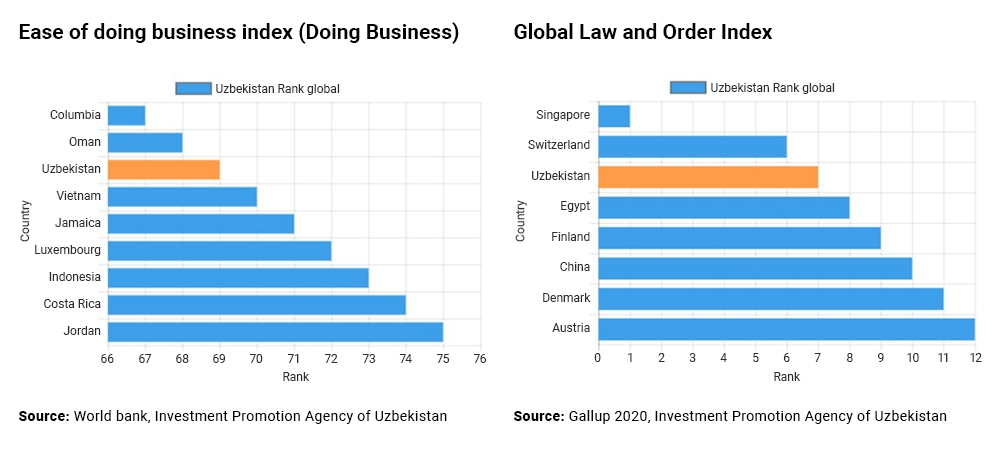

In a bid to reclaim the 36 million‑strong country’s centuries‑old status as one of the key centres of commerce along the Asia‑Europe trade routes, the Uzbek government has put in place a wide array of economic and social reforms to help support an inclusive transition to a private‑sector‑led economy. These include switching the Uzbekistani Som (UZS) to a free‑floating exchange rate in September 2017, introducing various new taxation rules aimed at simplifying the tax regime and reducing the tax burden on the economy since 2019, and cutting red tape and bureaucracy by reducing the number of executive bodies from 61 to 28 and ministries from 25 to 21 from 2023 onwards.

Through these measures, together with the extension of its economic cooperation with China as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Uzbekistan seeks to reinvent itself as a vibrant, linked‑in trade and investment destination along the route of the ancient Silk Road. The fastest‑growing Central Asian economy, which has enjoyed average GDP growth of nearly 8% per annum since the announcement of the BRI in 2013, also hopes to increase its economic weight in the region as it contributed only 20% of the region’s GDP last year.

In response to the nation’s strengthening economy and enhanced global connectivity, Uzbekistan, situated at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, is fast developing to become a preferred seat of arbitration in Central Asia and the wider Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region. This also reflects the growing demand for arbitration as a less confrontational means of settling disputes both locally and globally. At the core of the country’s alternative dispute resolution (ADR) development is the 2018 inception of the Tashkent International Arbitration Centre (TIAC).

To discover how Uzbekistan is evolving as a preferred seat of arbitration and how the latest exclusive arrangement between TIAC and Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) has helped oil the wheels, Louis Chan, Deputy Director of Research at HKTDC, sat down with Diana Bayzakova, Director of TIAC, and Sherzod Abdulkasimov and Temur Samarov, respectively founding partner and commercial lawyer of PraeLegal Uzbekistan.

Chan: What would you see are the key strengths of Uzbekistan as a preferred seat of arbitration? How would you compare TIAC with Kazakhstan's IAC? What are the distinct roles and competitive edges of TIAC?

Abdulkasimov: Uzbekistan is a country with a rich history and culture, and in recent years, it has emerged as a promising destination for international arbitration. As one of the world’s two double‑landlocked countries, Uzbekistan has unique characteristics that can help it grow into a preferred seat of arbitration.

One of the key strengths is its strategic location. Uzbekistan is situated at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, making it an ideal hub for international trade and commerce. Additionally, Uzbekistan has a large and growing economy, with a focus on sectors such as agriculture, mining and manufacturing. This presents significant opportunities for businesses and investors looking to do business in the region.

Another is its legal framework. The country has made significant progress in recent years to modernise its legal system in alignment with international standards, including the adoption of new laws and regulations, the establishment of specialised courts and the launch of arbitral institutions such as the TIAC.

When comparing TIAC with Kazakhstan’s International Arbitration Centre (IAC), it is important to note that both institutions have their distinct roles and competitive edges. Kazakhstan’s IAC has been in operation for a much longer time than TIAC and has also established a strong reputation in the region.

In addition to Uzbekistan’s strategic location in Central Asia, its growing economy, and a large and diverse consumer market, choosing TIAC to administer disputes would entail several unique advantages:

♦TIAC charges no fee to administer a dispute;

♦There is an opportunity to choose the method of compensating the arbitrators: either on an ad valorem or an hourly rate basis (to be agreed by the parties);

♦An internationally recognised legal framework governs the arbitration proceedings in Uzbekistan, which was declared by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) as model-law compliant;

♦There is no VAT on arbitrators’ services (and no income tax on arbitrator’s fees);

♦TIAC has a strong focus on technology and innovation, including cutting-edge arbitration procedures and services such as those related to the use of technical primers and experimental evidence.

One of the distinct roles of TIAC is to serve as a bridge between the East and the West. The institution has been striving to promote international trade and investment by developing and offering a range of services and initiatives to support businesses and investors looking to do business in Uzbekistan and the wider region. Additionally, TIAC has a strong commitment to promoting the use of technology in arbitration, which has helped it to attract a range of tech‑focused businesses, including start‑ups.

In conclusion, as a major player in Central Asia and along the Silk Road, Uzbekistan has significant strengths that can help it develop into a preferred seat of arbitration. With its strategic location, growing economy, and modern legal framework, the country is well‑positioned to attract businesses and investors looking for a reliable and effective dispute resolution mechanism. TIAC has a unique role to play in this regard, with its focus on technology, innovation, and international trade and investment, and it is poised to become a leading institution in the region and beyond.

CHAN: How are the Uzbek government and competent authorities supporting reforms, especially legal reforms to enhance international connectivity and recognition in order to underpin TIAC’s development? How international is TIAC so far? Is there a high demand for arbitration in Uzbekistan? What about the CIS region?

Abdulkasimov and Samarov: The Uzbek government and competent authorities have been taking significant steps to support legal reforms that enhance international connectivity and recognition, which in turn underpin the development of TIAC. These steps include:

♦Updating and modernising Uzbekistan’s legal framework in alignment with international best practices and standards. This includes the adoption of a new law on arbitration modelled on UNCITRAL law on international commercial arbitration, investment, and intellectual property, among others.

♦Promoting transparency and accountability in the legal system through measures such as the establishment of a public register of court decisions and the introduction of electronic case management systems.

♦Strengthening the capacity of legal professionals and institutions through training programs, partnerships with international organisations, and the establishment of new legal education institutions.

TIAC has been actively developing itself into an international arbitration centre and has been successful in attracting cases from different domestic and foreign parties. In making a firm commitment to its stakeholders and prospective users, TIAC has appointed a diverse mix of international experts on its panel of arbitrators to make sure that its proceedings are conducted in accordance with international standards of due process and fairness.

Despite the past few years of global pandemic, there has been a growing demand for arbitration in Uzbekistan and the wider CIS region. As businesses become more international and cross‑border transactions become more common, parties are increasingly seeking ADR mechanisms that are efficient, cost‑effective and impartial to provide a neutral forum for resolving disputes.

Chan: What are TIAC’s major sectors of specification? Industry‑ and/or geography‑specific? State‑State, Investor‑Investor or Investor‑to‑State?

Bayzakova: TIAC positions itself as a global arbitral institution providing services for a wide variety of disputes, including commercial, investment and other types of disputes. At the same time, it is important to note that TIAC’s 2021 Rules of Arbitration are particularly adapted for technology disputes with specific provisions on experimental evidence, technical primers, reference materials and tutorials as well as opt‑in cybersecurity rules. In 2020, TIAC received its first Request for Arbitration where neither party was from Uzbekistan – the claimant originating from Russia and the respondent from Singapore.

We believe language and geographical location are the key contributors to TIAC’s standing and success as an institution of choice for CIS disputes. Our services are available to both domestic and foreign parties, capable of administering disputes in a variety of languages.

Chan: What is TIAC’s track record so far? Are there any caseload statistics to show how the Centre has been received by international businesses?

Bayzakova: Since its establishment in November 2018 under the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Uzbekistan, TIAC has administered nearly 50 Requests for Arbitration, all of them being international in nature. These cases have included disputes relating to commercial contracts, joint ventures, construction projects, and investment agreements, among others. There have also been two applications for emergency relief, and one request for expert determination in connection with a project financed by an international financial institution.

Meanwhile, the geographical representation of the parties ranges from jurisdictions within the CIS region such as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Russia to jurisdictions from Europe such as Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands, Moldova and from the Far East such as China, Singapore and the Philippines.

Chan: How would you see Hong Kong and Uzbekistan, already linked through the Belt and Road Initiative, could work together to help international businesses wanting to do more trade in Central Asia? How would you expect the exclusive arrangement under the TIAC‑HKIAC Cross Institutional Arbitration Rules (TIAC‑HKIAC Rules), which came into force in September 2022, to help achieve this?

Bayzakova: Hong Kong and Uzbekistan both play important roles in the BRI, which helps promote economic connectivity and cooperation across the globe. As a financial and commercial hub in Asia, Hong Kong has the expertise and resources to support businesses looking to invest in Central Asia, while Uzbekistan offers abundant natural resources, a young and skilled workforce and an opportunity to do business in a growing and diverse market.

To foster Hong Kong‑Uzbekistan cooperation in the ADR front, the exclusive arrangement under the TIAC-HKIAC Cross Institutional Arbitration Rules (TIAC-HKIAC Rules) can help facilitate business activities in Central Asia and a wider CIS region by providing a seamless and efficient mechanism for resolving disputes that may arise between parties from different jurisdictions and offering local expertise in handling disputes with the regional nexus.

The TIAC‑HKIAC Rules provide a framework for the two institutions to collaborate and coordinate their activities in order to ensure that disputes are resolved in a timely and effective manner. Under this framework, TIAC and HKIAC will jointly administer cases and TIAC will refer to HKIAC on certain procedural issues arising in arbitrations filed pursuant to the Rules. HKIAC, on the other hand, will make its decisions without charging administrative fees, except in limited, pre‑defined circumstances. For example, issues of appointment of arbitrators or jurisdictional objections are to be decided by HKIAC, whereas issues of registering the request for arbitration, collecting payments and initiating the correspondence with the parties are to be dealt with by TIAC.

HKIAC’s extensive expertise in disputes involving Chinese parties and growing experience with CIS disputes, together with TIAC’s technological development strategies, will offer new dispute resolution opportunities for arbitration users across the CIS and Asian regions.

First, please LoginComment After ~