SOUTH AFRICA: A MODEL OF STABILITY OR STYMIED INNOVATION?

Fintech in South Africa is one of many caveats. A country with a highly banked population — yet one whose masses rarely use their accounts. A key financial and tech hub of Africa — yet with a wholly different financial services landscape compared to other African countries. South Africa’s advanced regulator breeds comparisons to countries like the UK and Australia at times, while the country deals with rolling blackouts.

Through it all, the country’s fintech ascendency — and surprising stability in the current environment — is providing a vital test case for how the fintech revolution permutates in an emerging market replete with a ubiquitous — yet underutilized — banking sector.

Slow And Steady Wins The Race?

With the second largest economy in Africa, South Africa’ presence can’t be ignored across the region. But South Africa’s market is its own unique creature. Consider M-Pesa’s quixotic earlier efforts to penetrate the South African market. Mobile money isn’t the foundation of the South African fintech ecosystem: traditional banks are.

Banks and fintechs in South Africa boast of South Africa’s banking sector as mature and robust, evincing stability and resilience over the years. South Africa’s “Big Four” banks — Absa Bank, First National Bank (FNB), Nedbank and Standard Bank — rule the roost. As Chipo Mushwara, emerging innovation and payments executive at Nedbank, puts it, the Financial Services Conduct Authority (FSCA) is one of the few regulators in the world with enough teeth to jail bankers for violating laws like the Financial Services Act.

On the one hand, the regulator’s more scrutinizing approach — along with the incumbents’ heavy penetration in the sector — have constrained innovation so that it’s more typically driven by the regulator or industry than at a grassroots level, says Mushwara. Considering the dynamic’s emphasis on legacy institutions, there isn’t the kind of “leapfrog” into digital financial services enjoyed in places like Kenya.

The payoff, however, has been greater stability even under macroeconomic duress — and credibility for its banking sector. Mushwara draws the greatest comparisons on the regulatory front to countries like the UK and Australia.

Due to the worsening macroeconomic conditions, including rising inflation and interest rates, rolling blackouts and a weakening currency, Nedbank recently said it expects a rise in non-performing loans. Considering Nedbank’s well-capitalized position, however, Mushwara expresses confidence in Nedbank’s ability to sustain these losses, as the bank even continues with financial inclusion efforts — if judiciously. At market scale, the centrality of big banks in South Africa’s ecosystem helps mitigate 2023’s macroeconomic fallout.

South Africa’s strong incumbent banking sector is unlike much of the rest of the continent. From purely an account ownership standpoint, South Africa stands out among its African peers. According to the World Bank’s Findex 2021, South Africa’s account ownership jumped 30% in a decade to reach 85% in 2021. Even among poor adults, account ownership is 78%, buoyed by the ease and ubiquity of banks and ATMs. 60% of first accounts in South Africa were opened to receive a wage or government payment, according to Findex’s 2021 Database.

Reconciling Data With Reality

But these outstanding numbers in account ownership in South Africa belie account usage realities. As Mushwara explains, many in South Africa treat their accounts as like “post boxes,” storing money when wages are received, only to shortly after withdrawing money and storing it elsewhere as cash.

Andres Perez, the co-founder and director of the Fintech Association of South Africa, frames the problem as hearkening to the lack of digital and financial literacy often in disadvantaged townships. At first glance, insurance rates can appear misleadingly high when it largely comes in the form of funeral insurance; other forms of insurance are still underutilized.

A Race To (Which) Bottom?

The efforts among incumbents, challengers and fintechs, consequently, are two-fold: outcompete the “fierce competition” brewing for customers and expand consumer usage and understanding of financial services. Nedbank is taking great efforts to increase their foothold in the township economies, which are often cash-based and underserviced, as a means of growth in the at least superficially saturated market.

Incoming challengers and fintechs are targeting the lesser served segments as well.

The ecosystem of financial service providers — tier one banks, smaller banks, challenger banks, fintechs and payment service providers (PSPs) — are coalescing in a partnership-driven system. But Perez says partnerships from the big banks often remain limited.

By contrast, racing ahead on such efforts are the most successful challenger banks — among them TymeBank, NuBank, Access Bank and Discovery Bank — that utilize third-party partnerships to extend their capabilities without mounting expenses, including partnering with physical retailers, allowing them to compete with the big banks while pressuring them to digitally innovate.

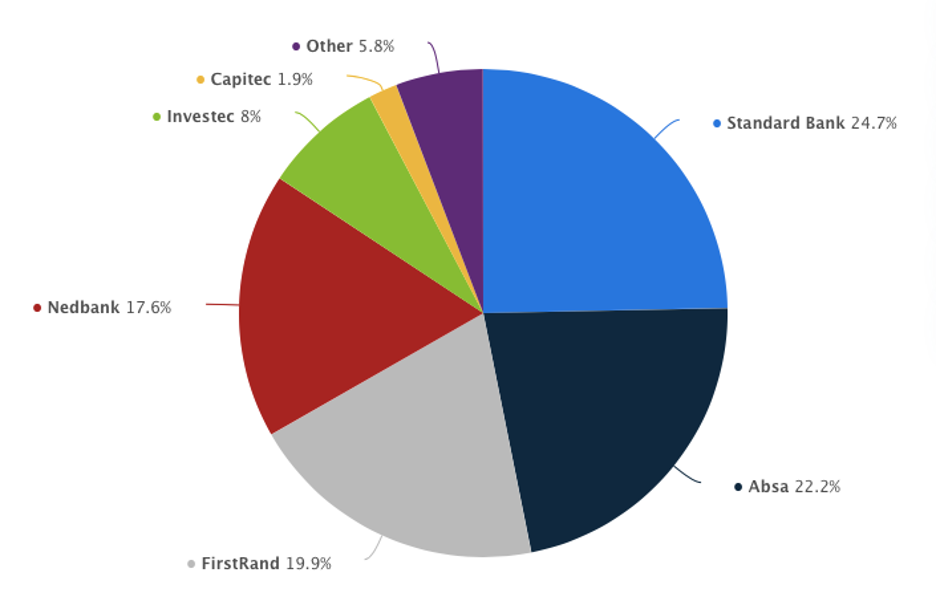

Nonetheless, considering their market dominance — about 84% of market share in 2021, according to Statista — tier one banks remain the prize partnerships for fintechs and PSPs.

Market share of leading South African banks, 2021

Though coming along slowly, the big banks are warming up to leading PSPs like Flutterwave as partners. Flutterwave is the leading B2B payments aggregator in Africa, stretching across 40 markets. According to Paul Harris, as recently as three or four years ago, the big banks didn’t even have APIs. Now, they are building their own APIs along with value-added services. Some of them now partner with Flutterwave as a vehicle to facilitate payments with the rest of Africa through one API.

Mama Banks And Baby Fintechs

Much of these partnerships revolve around the drive to usher in embedded financing or open banking driven by APIs. Akin to digital banks like TymeBank, incumbents like Capitec and Nedbank have followed through with their own open banking-esque super app options, through Capitec Pay and Avo, respectively.

But progress has been slow, following the regulator’s pace. The FSCA takes its time studying an emerging issue before releasing a position paper stating their vision for market innovation. Stakeholders note while the FSCA lays down a vision in these papers, inconsistent interpretation can produce different outcomes. Invariably, however, the onus falls on the banks to follow through on issues regarding stability, data and privacy.

For the time being, South Africa’s regulatory framework is in anxious anticipation for the CoFi Bill, which will potentially expand compliance requirements to more financial service providers while shifting to a principles-based approach prioritizing fair treatment and protection of customers.

The most recent regulatory step taken to enable innovation came this spring with the launch of PayShap, the national rapid payment platform. However, some stakeholders find it unlikely to have the kind of rapid adaption of instant payments experienced in places like Brazil. Currently, PayShap is only peer-to-peer, and transactions are not mandated to be free. While big banks — the only four to have initial integration — note some early uptake, the payments market hasn’t ignited.

Perez and Harris find PayShap’s consumer costs and lack of integrations to be symptomatic of the big bank-dominated terrain. While PayShap is expected to expand to other PSPs soon, at this point, it is up to narrow market competition to drive down prices. Currently, FNB charges R.65 per transaction over R100 and Nedbank only R1 or R7.50 for transactions up to R3,000, but Standard Bank and Absa charge substantially more.

Such trends repeat the mistakes of other places like Poland, where the banks were able to dictate the cost of transaction fees. In South Africa, ETFs often remain more attractive than instant payments from a cost standpoint.

“Open banking” at this point remains more a concept than a fully realized idea. The FSCA still doesn’t allow banks to share data with MNOs or retail banks, limiting the value they can offer consumer clients. Data sharing is kept at a very small scale between institutions rather than a global scale.

Slow, Smooth Sailing?

While an incumbent-driven, regulator-empowered environment may minimize out-of-the-box innovation, the stability it provides appears more pronounced now amidst fintech’s choppy fiscal waters. Perez notes that South Africa’s fintechs have experienced far less layoffs than elsewhere during the global fiscal decline. Even before recent turbulence, at times stringent capital requirements fostered a fintech culture in South Africa where rather than burning through money, digital financial upstarts proved their resourcefulness right away.

That resilience, combined with the strong banking sector and emerging fintechs in the competitive market, bodes well for South Africa’s future. With stakeholders mostly praising the regulator’s astute approach, its deliberate pace suggests that eventually, South Africa will get it right — even if initial forays in open banking and instant payments repeat the mistakes of certain bank-dominated markets that impede adoption.

Ultimately, the banks’ revenue continues to primarily rely on the basics like deposits and lending.

First, please LoginComment After ~