Does Sustainable Finance Regulation Play a Role in the “Greening” of Capital Markets?

Download → English PDF

Abstract

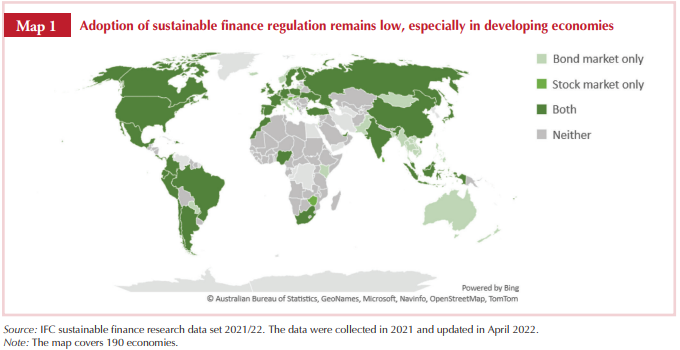

Robust regulatory frameworks are important for developing healthy capital markets. Most current research ends that sustainable finance regulation serves as a backbone for the development of sustainable bond markets. Conversely, some argue that such regulation is not essential for effective greening of capital markets. This Brief presents results from a novel global sustainable Finance regulatory data set. Worldwide, adoption of sustainable Finance regulation remains low. Yet, there is a strongpositive relationship between the number of issued corporate green bonds and (1) the presence of sustainability factors in stock markets' regulatory frameworks, (2) having sustainability reporting as a listing rule on a local securities exchange, (3) regulatory guidance on sustainability reporting, and (4) issuance of annual sustainability reports by securities exchanges or regulatory agencies.

A strong enabling regulatory framework is an important element for the development of healthy markets for sustainable nance. Market regulations intend to ensure predictable, orderly, and trustworthy interactions among di erent market players. Without enforceable regulation, market participants can nd ways to circumvent common market principles and engage in opportunistic and disruptive behaviors. Well-designed sustainable nance regulation improves market competitiveness, innovation, and growth (Ambec et al. 2013). Further, research shows that institutional quality and rule of law are important indirect drivers of green bond market capitalization (Tolliver et al. 2020a).

Most current research nds that national-level regulation of sustainable nance is a backbone of the development of sustainable bond markets. e International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) de nes the following types: green bonds are any type of bond instrument where the proceeds or an equivalent amount will be exclusively applied to nance or re nance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible green projects; social bonds are use-of-proceeds bonds that raise funds for new and existing projects with positive social outcomes; sustainability bonds intentionally are applied to a mix of eligible green and social projects; and sustainability-linked bonds are any type of bond instrument for which the nancial and/or structural characteristics can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves prede ned sustainability/ESG (environmental, social, and governance) objectives.

Sustainable nance regulation signals to bond issuers that climate and green sectors are commercially viable (Park and Kim 2020); communicates clear information about thematic bonds as well as their underlying criteria and standards (Ridzak and Zigman 2020); and o ers direct incentives for the issuance of sustainable nancial instruments (Tuhkanen 2020). In turn, a functioning market for sustainable nance could also boost innovation, changing corporate behavior and even culture by incentivizing issuers to transform conventional bonds into sustainable ones (Flammer 2019). Overall, sustainable nance regulation enhances investor con dence in sustainable nance instruments. Sustainable regulatory changes and the introduction of sustainable bond certi cation frameworks are often considered to be a rst step in building green bond markets in emerging economies (Tyson 2021).

Another strand of research, although less prominent than the rst one, argues that the regulation of sustainable nance is not an essential element in building strong markets for sustainable bonds. In this opposing view, sustainable bonds are no di erent from conventional “plain-vanilla” bonds and hence do not necessitate a separate regulatory framework. A study using a cross-country analysis nds that the same institutional and macroeconomic factors that a ect conventional bond market growth have the same impact on sustainable bond markets (Tolliver et al. 2020a). If comprehensive and well-designed general capital market regulation is put in place, there is no justi able need for introducing separate sustainable nance regulations (Reboredo 2018). Furthermore, the development of capital markets is primarily associated with overall economic growth (Greenwood and Jovanovic1990). According to these views, as long as economies have healthy macroeconomic environments and steady economic performance, their capital markets should develop well regardless of the existence of sustainable nance regulation. However, these studies have not been done on a large scale and hence might be driven by the sample size and the underlying assumptions. For example, none of these papers consider whether or not sustainable nance regulations were introduced or what a counterfactual would be.

Currently, most sustainable nance markets are governed by voluntary principles and sustainability-oriented institutions rather than traditional regulatory standards. To ll this regulatory gap, international associations and nongovernmental entities, such as the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) and the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), have assumed a role traditionally assigned to policy makers and regulatory agencies. ey took it upon themselves to develop Green Bond Principles as well as Climate Bonds Standards and Certi cation Schemes to facilitate development of strong and transparent sustainable nance markets. However, such third-party guidelines for sustainable nance regulation may result in a lack of consideration for the nuances and functionality of local capital markets. Regulations that are well-suited for mature capital markets might not be as relevant to nascent markets, for instance.

In addition, third-party sustainable nance market guidelines are not as e ective at preventing “greenwashing” as national-level regulation. e existence of multiple sustainable nance standards and guidelines enables companies to pick and choose guidelines that are most suitable to their corporate interests (Park 2018). Consequently, rms can evade entire sets of sustainable regulations, such as proper disclosure and impact reporting, while bene ting from lax green classi cations of issued nancial instruments. e lack of enforceable standards and a high risk of greenwashing, where companies selectively apply sustainable standards without making substantive change, disincentivizes both sustainable issuances and investments (Deschryver and de Mariz 2020). When transparency and disclosure of sustainable issuances are enforced by a national regulation, with clear repercussions for noncompliance, this gives more credibility to sustainable nance markets. If there is a market-wide lack of investor trust in sustainability instruments, such a market is unlikely to grow.

Adopting sustainable nance regulation could help developing economies cultivate local markets for sustainability instruments. Many developing economies, such as Algeria, Angola, Chad, the Republic of Congo, the Russian Federation, and Zambia are highly dependent on natural resources (World Bank Group 2020). is dependency makes the incorporation of environmental and social risk management into nancial market regulatory frameworks important for long-term economic growth. Yet, developing economies tend to have weak regulatory institutions and low enforcement capacity, coupled with high market volatility. ese market characteristics lower investor con dence, driving down demand for sustainability instruments. In general, demand for sustainability instruments in developing economies is comparatively low, mostly due to their limited investor base, resource constraints, and lack of general commitment to environmental sustainability. Hence, in such cases, national-level sustainable nance regulation could scale up sustainability markets by building investor con dence by ensuring compliance with the set standards and demonstrating regulatory commitment to sustainable nance.

Some sustainable nance markets operate on voluntary principles and initiatives driven by the private sector. In 35 economies, mostly from the high-income OECD group (24 out of 35), sustainability factors are captured in voluntary industry principles or practices (IFC ESG data set) (see box 1). Without waiting for regulatory sustainability mandates, multiple corporations have taken the initiative to design their own green and social bond frameworks to raise sustainable nance, attracting impact investors. For example, a private company in Argentina—Mercado Libre Inc.—developed a corporate sustainable bonds framework in 2020. e company hosts the largest online commerce and ntech ecosystem in Latin America with a presence in 18 economies, including Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and República Bolivariana de Venezuela. e company has created the framework to allocate the net proceeds from the issuances of green debt securities to projects that render environmental and/or societal bene ts. e company’s framework is aligned with the ICMA principles (ICMA 2021). In 2016, the Mexican Association of Banks presented a sustainability protocol consisting of ve strategic areas including environmental and social risk management, and e cient use of resources. is protocol was signed by 22 out of 52 banks in the country (Leo et al. 2019).

......

Author(s)

Saltane, Valentina

Amin, Anam

Farazi, Subika

First, please LoginComment After ~