Monetary policy as engineering?

In her first speech as Deputy Governor for Financial Stability and as a member of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), Sarah Breeden sets out her view on the UK economic outlook and outlines her approach to monetary policy. She describes how against a backdrop of unprecedented shocks, she intends to approach monetary policy by paying attention to how real world outcomes differ from expectations and using scenario analysis to guide policy.

This is my first speech as a Deputy Governor and member of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the Bank of England. I am going to use the speech to describe my approach to monetary policy and how I am applying it to the situation the MPC currently finds itself in. I can think of few better places to do so than a ‘Talking Policy’ seminar, and I am very grateful to have been invited along to speak to you all today.

I will focus on a few important questions. Where is the economy now? How did we get here? What could happen next? What does that mean for my approach to monetary policymaking? And finally, why is that approach the right thing for the economy?

Where is the economy now?

Monetary policymakers like to talk about uncertainty.1 But it is fair to say that working out what the state of the UK economy is and where it's heading is especially uncertain at the moment. There are measurement issues2 , volatility in the data and exceptionally large data revisions. 3 The bottom line is that it is more difficult to extract a clear signal from the noise.4 That said, I will start by briefly painting a picture of what I think is happening in the economy in general terms.

First, economic activity has been practically flat since the end of 2022. That is of course stronger than the MPC and other forecasters expected this time last year, in part because of the adjustment to energy supply headwinds and the steep fall in energy prices since then.

But in historical terms it is very weak. GDP has grown by about 0.5% over the past year, which compares to average annual growth of 1.5% since the Global Financial Crisis – itself a period of low growth by historical standards. 5. Second, the labour market is loosening but it remains tight. The survey-based employment indicators point to a tentative slowdown in hiring. The level of vacancies has fallen from a peak of 1.3 million in the middle of last year to just under a million in the latest data. But that is still more than 100,000 above its pre-Covid level, which itself was elevated by historical standards. And importantly, whilst wage growth has finally begun to fall it is still greater than 7% on most measures, which given the current weakness in productivity growth in the UK is several percentage points higher than a level that, if sustained, would be consistent with the inflation target.6

Third, inflation has been falling over the past year but it remains far too high. It peaked at 11.1% in October 2022 and was 4.6% in the October data. A naïve calculation would imply that we have done more than two thirds of the work to get inflation back to target.

But much of the fall in inflation so far owes to base effects: the mechanical counterpart of the unprecedented increase in the level of energy prices that came to an end just over a year ago, with a much smaller contribution so far from the significant monetary policy tightening.7 Taken at face value, the MPC's November forecast implies that inflation will not return to the 2% target for another two years, so we expect to have a way to go.

How did we get here?

It is worth stepping back to review how we got here. I think a few points of context are particularly important to bear in mind.

First, the UK economy has been hit by a series of unprecedented shocks.8 The UK’s departure from the European Union coincided with a once-in-a-hundred year pandemic during which much of the UK and global economies were shut down. The process of reopening those economies met with supply chain frictions that pushed up materially on the prices of globally traded goods. Then in 2022 Russia staged an unprovoked and unjustified invasion of Ukraine, starting the biggest war in Europe for 80 years, and pushing up European energy prices by many multiples as a consequence. Most of these shocks – but of course not all of them – have affected other advanced economies too. All have contributed to volatility in economic activity and inflation.

Second, high inflation since 2021, which was initially caused by imported goods and energy prices, has led to the emergence of second-round effects on wages and prices in the UK. 9 This process has been supported by exceptional tightness in the labour market, and has been stubborn even in the face of the shocks I just described. These second-round effects have contributed to persistence in inflation in the UK and, albeit to a lesser extent, in other advanced economies.10

Third, demand has been resilient and supply has been very weak. The tight labour market and elevated inflation – especially for goods and services that tend to have a larger domestic cost component – point to a UK economy that is operating at or above capacity. But the data suggest that economic activity has been flat. That implies that supply has been very weak, which is a natural consequence of some of the shocks I mentioned earlier.

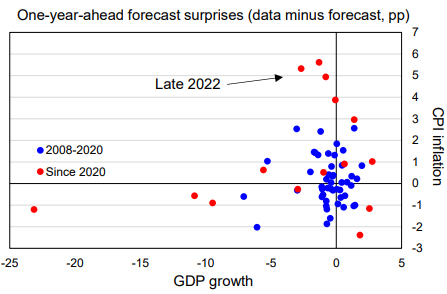

These have combined to deliver a series of significant forecast surprises in the UK and other advanced economies. Focusing on the UK, until very recently inflation had been much higher over the past couple of years than we had expected. And as I said before, economic activity has been more resilient than we expected. Chart 1 shows that the scale of these surprises – based on one-year-ahead forecasts – has been larger than at any point since the Global Financial Crisis.11 Some of the surprises, for example in late 2022, looked like textbook supply shocks, with stronger inflation coming at the same time as weaker GDP. More recently GDP has been much stronger than our forecasts a year ago, with inflation weaker than expected, suggesting some unwind of prior supply shocks.

Chart 1: Over the past few years the MPC have had to deal with larger forecast surprises than at any point since the Global Financial Crisis (a)

Source: Bank of England, ONS

(a) The chart shows the difference between quarterly data outturns for year on year growth in GDP and CPI inflation and the MPC’s modal forecast for those variables made one year earlier. The forecasts condition on market expectations for Bank Rate, energy prices and other factors at the time the forecasts were made.

In general these surprises tend to have been serially correlated – particularly for inflation – meaning that positive surprises tend to have been followed by further positive surprises.12 These large inflation surprises have been common across advanced economies, including the US and the euro area.

To state the obvious, this context has made monetary policymaking difficult. I have learned two important lessons. First inflation and wage growth have been stronger than our models would have predicted, suggesting greater second-round effects than I would have expected before this inflationary episode. Second, there is more uncertainty than usual about the speed and scale of the monetary transmission mechanism, especially given the unprecedented tightening we have seen.

What I take from this is that we are in a state of the world where monetary policymaking is best considered as engineering rather than science. The shocks and data surprises are too large for us to have any hope of understanding the detail of what is happening in a complex system and fine tuning economic outcomes through our models. Instead – like engineers – we should pay attention to real world outcomes and adjust accordingly. 13

That means we have had to remain open-minded to make sure that we continually learn how the economy is responding to these shocks. We have had to remain humble about how well economic models perform when movements in important variables are ‘out of sample’ – in other words historically unprecedented. We have had to place more emphasis than usual on what we know has happened, or is happening, in the economy and acknowledge that future projections are more uncertain than usual.14 And given the uncertainty around the things we are simply unable to observe but that matter a lot now for policy – most obviously trends in supply – we have had to rely more on extracting signals from so-called ‘late cycle’ indicators, such as inflation and wage growth, rather than indicators of economic activity. 15

One approach that I think helpful is to think through a range of possible scenarios for the UK economy, where those scenarios reflect how real world outcomes have differed from our expectations – our lessons learned from engineering, if you like.

......

First, please LoginComment After ~