Monetary and fiscal policies as anchors of trust and stability

Download → PDF full text

Introduction

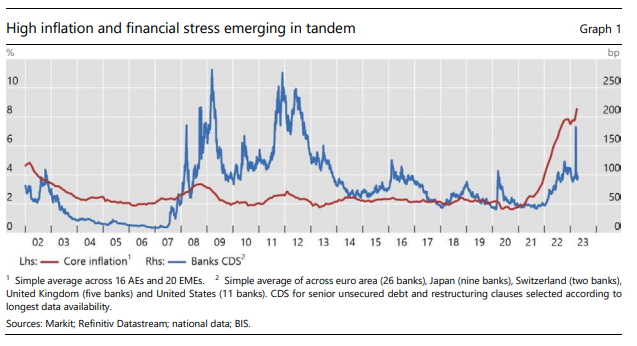

It is a pleasure and an honour to speak to you today. We are living in extraordinary times … once again. Over the past two years inflation has surged (Graph 1). Its rise has been large, sudden and global. In many parts of the world, it is now at levels unseen for generations. Meanwhile, financial systems have come under strain. Recent bank failures are the most prominent example, but far from the only one. For the first time in recent decades, we are seeing high inflation and financial stress emerging in tandem (Graph 1)

High inflation and financial stress each have their own specific immediate causes. But, in my view, they are a symptom of a broader and deeper problem. Monetary and fiscal policy have tested the boundaries of what I call the “region of stability”.

This region refers to the constellations of monetary and fiscal policy that, conducted over time, support macroeconomic and financial stability and keep the inevitable tensions between the two policies manageable. Staying clearly within this region prevents them from damaging the economy through inflation, financial stress and slumps. And it allows them sufficient headroom to deal with unexpected shocks that can cripple the economy and, in the process, the policies themselves.

The region’s boundaries are elusive. They cannot be summed up in simple metrics, like a limit for the ratio of public debt to GDP or the policy interest rate. The region evolves over time, influenced by long-run political and technological forces that shape the structure of production and finance. Macroeconomic policy settings can themselves alter the region’s boundaries, if kept in place for long enough.

The recent challenge to the boundaries is the latest in a long journey that stretches back at least to the 1970s. At each step, the policy choices seemed reasonable, even compelling. But cumulatively, they have brought us to an extraordinarily complex place. This reminds us that economic systems can appear stable until, suddenly, they are not. Challenges to the boundaries of the region may become fully apparent only ex post.

Let me explain.

Powerful secular tailwinds such as globalisation masked what had once served as a key signal that policies were testing the region’s limits – high inflation. The dynamics of financial liberalisation gave rise to a new signal – financial instability. Quiescent inflation fostered the belief that monetary and fiscal policy could smooth out every economic downturn and prolong expansions with little constraint. Strong stimulus was deployed in recessions but there was little normalisation and rebuilding of policy buffers when growth resumed. The pattern became starker after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and the pandemic-induced recession when extreme uncertainty prevailed, economic activity collapsed, and inflation hovered stubbornly below target.

Given the circumstances, it seemed natural that authorities could use their policies to promote growth without stoking inflation. But their ability to do so relied on aggregate supply adapting smoothly to changes in aggregate demand. This was the case for some time, but when the Covid pandemic rendered supply conditions unusually inflexible, the magnitude of the risks that were unknowingly taken became all too apparent.

Thus, a shift in policy mindset is called for. Returning firmly inside the boundaries of the region of stability should be a conscious and explicit policy consideration.

Let me elaborate on these thoughts. First, on the roles that fiscal and monetary policies have played in causing and addressing the immediate challenges of inflation and financial instability. And second, on the forces that led policymakers, at various times in the past, to approach the boundaries of the “region of stability”. I will then conclude with some reflections on how we could return to a more comfortable location within the region.

First, please LoginComment After ~