A positive neutral rate for the countercyclical capital buffer – state of play in the banking union

This article discusses the possible implementation of a positive neutral rate for the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) as a means of increasing macroprudential policy space in the European banking union. Drawing on experience from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, it explains why a positive neutral rate is needed to enhance the effectiveness of the current macroprudential framework. It also describes recent progress on the application of this tool around the globe and concludes with some remarks on the calibration and potential future application of the tool in the banking union.

1 Lessons learned on capital buffers during the pandemic

Experience from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has sparked further discussion on the functioning of bank capital buffers, although the banking system has proved to be resilient overall. Banks continued to perform their core functions throughout the COVID-19 crisis, which included ensuring a constant flow of credit and avoiding adverse feedback loops between the financial system and the real economy. This was also due to the comprehensive policy response – in the form of strong monetary, fiscal and prudential support measures – which prevented credit risk from materialising at an aggregate level. Given the impact of these extraordinary support measures, questions have arisen about how the prudential framework would have worked in their absence. One of the focal points of this debate is the functioning of capital buffers, which are placed on top of minimum capital requirements and subsumed in the combined buffer requirement (CBR). These buffers are meant to act as shock absorbers, enabling banks to absorb losses while continuing to provide key financial services to the real economy in times of stress. However, several observations from the pandemic suggest that buffers may not be fully effective in meeting this objective under the current set-up.

First, evidence from the pandemic suggests that banks may be unwilling to “dip into” their non-released capital buffers when losses materialise, which means that the buffers may not fulfil their intended role as shock absorbers. The Basel framework specifies that capital buffers “can be drawn down as losses are incurred”, and that banks should be able to “conduct business as normal when their capital falls into the conservation range”. Accordingly, in the early stages of the pandemic, prudential authorities made considerable efforts to reassure banks that the buffers could be used in case of need. However, empirical evidence using micro-level data shows that proximity to the CBR was associated with lower growth in credit supply and stronger risk weight reductions over the course of the pandemic, both of which helps limiting potential reductions in risk-weighted capital ratios. This did not result in any credit supply constraints at the aggregate level, thanks in part to the extensive support measures that prevented widespread loss materialisation. Nevertheless, it suggests that banks are reluctant to use their capital buffers, preferring to maintain some headroom above the CBR to safeguard against a potential breach should losses materialise. This has the potential to induce broader systemic and adverse effects in terms of reduced credit supply, for example in scenarios where a larger share of banks experience losses and subsequently become capital-constrained.

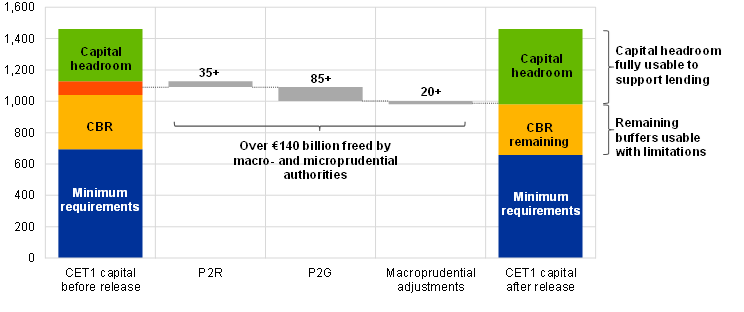

Second, releasable buffers such as the CCyB effectively reduce concerns about buffer usability, although the build-up of buffers explicitly intended for release was very limited prior to the pandemic. Following the release of a capital buffer, banks can operate with lower capital ratios without breaching the CBR, so that possible impediments to buffer usability – for instance relating to market stigma or automatic distribution restrictions – are reduced or removed. Couaillier et al. (2022b) show that the prudential capital relief measures in the banking union effectively supported bank credit supply during the pandemic, consistent with lower concerns about relative balance sheet expansions that reduce capital ratios.The effects of the relief measures were particularly strong for capital-constrained banks with little capital headroom above the CBR, suggesting that the relief prevented reductions in lending that could otherwise have resulted from banks' reluctance to breach the CBR. However, as shown in Chart 1, the bulk of the relief was provided by ad hoc microprudential adjustments, some of which did not reduce the threshold at which automatic distribution restrictions kick in.Banking union authorities released more than €140 billion in capital, amounting to roughly 1.5% of aggregate risk-weighted assets. However, only €20 billion of the release was due to macroprudential adjustments, of which only €6 billion was due to domestic CCyB releases. The main reason for this striking imbalance is that the build-up of macroprudential buffers had been very limited ahead of the pandemic, so macroprudential authorities had little ammunition to provide relief to the banking sector when the shock occurred. While the capital relief worked as intended, it was not provided via the measures originally envisaged for this purpose, and it cannot be taken for granted that similar ad hoc microprudential adjustments (such as the frontloading of the change in the composition of the Pillar 2 requirements (P2R)) would be available in future crises.

Chart 1

CET1 capital stack before and after prudential actions in response to the pandemic

(EUR billions)

Sources: COREP, national authorities.

Notes: The data refer to the fourth quarter of 2019 and include significant and less significant institutions consolidated at the euro area level. Policy decisions up to 31 March 2020 are included. The P2R adjustment refers to the frontloading of the change in P2R composition under the CRD V; macroprudential adjustments include releases of the CCyB, SyRB and O-SII buffers. Revoked announcements of CCyB increases or delays in the phase-in of measures (O-SII buffers, Article 458 of the Capital Requirements Regulation, CRR*) are not included.

*) Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 1).

Overall, the experience from the pandemic suggests that the role of releasable macroprudential capital buffers needs to be enhanced to effectively address adverse systemic shocks that can occur independently of a country’s position in the financial or economic cycle. Health emergencies such as the pandemic, as well as natural disasters, wars and shocks arising from climate change, political events or technological disruptions, may happen at any stage of the cycle. They can negatively affect the banking sector and lead to disruptions in the financial intermediation function, with adverse repercussions for the broader economy. Given the concerns about the usability of structural buffers such as the CCoB, releasable macroprudential buffers are particularly important for addressing such shocks, as their release effectively helps banks to fulfil their core economic functions. However, the CCyB, as the main releasable buffer, is currently geared towards addressing cyclical systemic risks associated with the domestic credit cycle, with its build-up conditional on variables indicating excessive credit growth. The framework therefore fails to account for the observation that releasable capital buffers may also help to absorb systemic shocks unrelated to the unwinding of domestic imbalances.

2 Increases in countercyclical capital buffers after the pandemic

In the light of the above, several macroprudential authorities in the banking union have started to make more active use of the CCyB in the aftermath of the pandemic. By the end of 2022, 12 out of the 21 banking union countries had set a positive rate for the CCyB, compared with only eight countries having positive CCyB rates at the end of 2019 (Chart 2). Reflecting the more active use of the instrument, the weighted (by risk-weighted assets) average of announced CCyB rates in the banking union, increased to 0.56% in the fourth quarter of 2022, up from 0.23% in the fourth quarter of 2019. The gradual CCyB tightening was initially supported by favourable macro-financial conditions, with signs of a robust economic recovery after the pandemic. However, tightening continued after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, despite the challenging and highly uncertain environment characterised by inflationary pressures and a deterioration in the economic outlook. These CCyB increases late in the financial and economic cycle were aimed at preserving banking sector resilience, with existing capital headroom seen as a key factor mitigating the risk of procyclical effects from the tightening. As a result, authorities now have greater leeway to make capital available for use when needed by releasing the accumulated buffers in the event of adverse shocks. This, in turn, can boost banks’ capacity to absorb losses while continuing to provide key financial services to the real economy when most needed.

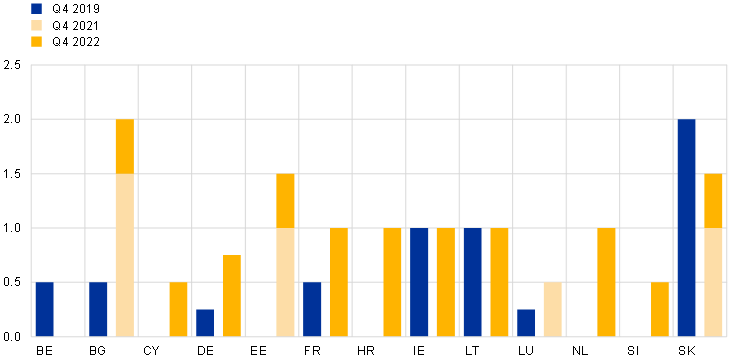

Chart 2

CCyB rates in banking union countries

Announced CCyB rates before and after the pandemic

(y-axis: CCyB rates as a percentage of risk-weighted assets)

Source: Macroprudential measures notified to the ECB.

Note: The chart shows announced CCyB rates in banking union countries that activated the tool either before the pandemic (in the fourth quarter of 2019) or after the pandemic (in the fourth quarter of 2021 or the fourth quarter of 2022).

The decisions to (re)activate the CCyB reflect risk-based considerations and a desire to enhance the role of releasable capital buffers, including by establishing a positive neutral rate for the CCyB in some countries. In several countries, a positive CCyB rate was warranted by the cyclical systemic risks identified, for example in relation to high credit and real estate price growth or elevated private sector indebtedness. In addition, thanks to the range of support measures, cyclical developments were less disrupted by the pandemic than originally expected, and, as losses did not materialise, some countries sought to restore pre-pandemic CCyB rates. Given the high uncertainty in the macro-financial outlook, increasing capital buffers also provided a signal to banks to remain prudent on distributions and maintain sufficient capital to be able to finance the economy in all phases of the financial and economic cycle. Finally, several countries revised their framework for the CCyB to include the possibility of setting a positive rate when cyclical systemic risks are not yet elevated, in other words a positive neutral CCyB rate. This allows these countries to start building up the CCyB earlier in the cycle, increasing the likelihood of it being available for a release when systemic shocks occur.

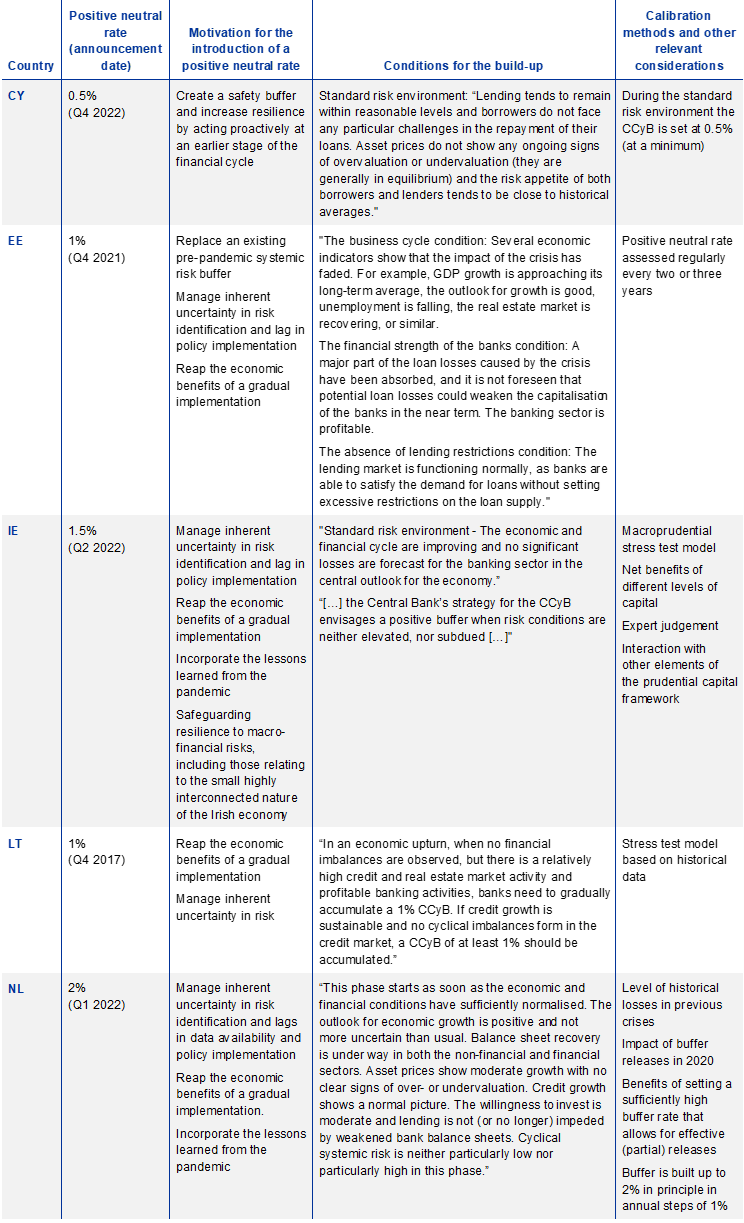

Decisions to introduce a positive neutral rate for the CCyB reflect the lessons learned from the pandemic and are to be seen in the context of a broader international move towards more active use of this instrument. Frameworks including a positive neutral rate for the CCyB are currently in place in five banking union countries, namely Lithuania since the end of 2017, Estonia since the end of 2021, and Ireland, Cyprus and the Netherlands since 2022 (see Table 1).

Authorities in these countries made a commitment to act earlier in the financial cycle so the CCyB rate will already be positive in “normal” times when cyclical systemic risk is not yet elevated (Figure 1). This rate can then be further increased as cyclical imbalances build up.This approach enables macroprudential authorities to provide relief to the banking sector via a buffer release in a wider set of adverse scenarios, thus reducing the need to resort to ad hoc support measures such as many of those enacted during the pandemic. The benefits of establishing a framework with a positive neutral rate have also been recognised by several countries outside the banking union (see Box 1), and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has voiced support for authorities using the tool.

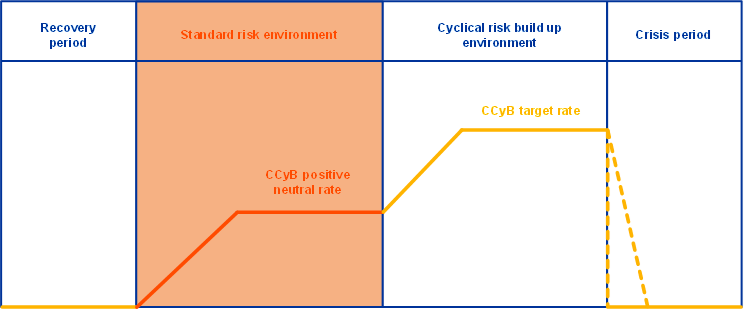

Figure 1

Stylised representation of a CCyB framework with a positive neutral rate

Source: ECB illustration.

Notes: This chart illustrates the setting of CCyB rates over the financial cycle applying the concept of a positive neutral rate. The two dashed lines at the very right indicate that a release of the buffer in crisis periods can either be gradual or in full.

The CCyB frameworks of countries that have introduced a positive neutral rate have some elements in common but also differ on several aspects. As illustrated in Figure 1, authorities usually distinguish among four stages of the financial cycle. CCyB activation and a gradual build-up of the buffer start in the “standard risk environment” stage, and the CCyB is further tightened in the subsequent stage when cyclical systemic risks increase. Table 1 shows that the definition of a standard risk environment differs slightly depending on the country, although in all countries the definition includes measures of macroeconomic, credit market and banking sector conditions. As regards the calibration of the positive neutral rate, authorities rely on different approaches. These include, for instance, analyses of historical losses, stress test models, assessments of the impact of buffer releases during the pandemic and expert judgement. The relative importance of different factors and calibration methods varies across countries, resulting in considerable variations in the chosen reference rate. Specifically, the positive neutral rate is set to 0.5% of risk-weighted assets in Cyprus, 1.0% in Estonia and Lithuania, 1.5% in Ireland and 2.0% in the Netherlands. In several cases, the level of the positive neutral rate may be revised over time to take on board insights gained from the accrued experience with the framework. However, adjustments would be considered only occasionally to ensure continuity and make capital planning easier for banks.

Table 1

Features of national CCyB frameworks with a positive neutral rate

(positive neutral rate expressed as a percentage of risk-weighted assets)

Sources: National macroprudential authorities' websites and relevant publications.

3 Key design issues to be addressed

Despite the recent more proactive use of the CCyB, additional progress on the application of the tool is needed over the years ahead, including further consideration of the setting of positive neutral rates. As explained in the previous section, banking union countries have made substantial progress on CCyB activation in the short period since the pandemic, despite the challenges brought by the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Nevertheless, although the weighted average CCyB of 0.56% is almost double the rate seen at the end of 2019, it is still considerably lower than the overall amount of capital released during the pandemic (1.5% of risk-weighted assets; see Section 1). In addition, several countries have not yet activated the CCyB at all. Further progress will therefore be needed in the years ahead. Key issues warranting further consideration are the calibration of potential positive neutral buffers and the degree of harmonisation in the use of positive neutral rates across banking union countries.

The calibration of the positive neutral rate for the CCyB needs to balance several factors. On the one hand, the rate needs to be high enough for its release in the aftermath of a shock to have a meaningful impact and to effectively support banks in absorbing losses while continuing to provide key services. The Basel framework already foresees a sizeable amount of releasable or effectively usable capital buffers, motivated by historically observed banking sector losses and stress test approaches.However, the shortcomings identified in Section 1 suggest that in practice this amount may be substantially lower than envisaged, so that the role of releasable buffers needs to be stepped up. On the other hand, the implementation of a positive neutral rate should not result in procyclical adjustments by banks, especially in the current, challenging macro-financial environment. Therefore, implementation may need to be gradual and account for the prevailing banking sector conditions and country-specific factors. In addition, the calibration of the rate itself may also need to take country-specific factors into consideration.

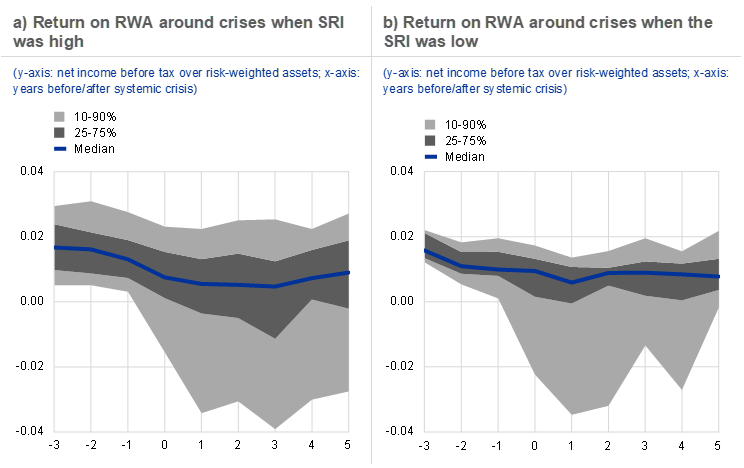

An analysis of historical bank losses supports the notion that, over the course of the cycle, CCyB rates will need to be substantially higher in the future. As illustrated in Chart 3a, a substantial share of banks suffered material losses in crisis episodes that were preceded by a pronounced build-up of cyclical systemic risk. This share of banks is lower, but still sizeable, in countries where cyclical systemic risk was below common signalling thresholds before the crisis (Chart 3b).The implications of these observations are twofold. First, CCyB rates will need to be increased substantially over the cycle to effectively support loss absorption and the provision of key financial services when shocks occur after boom episodes, particularly considering that non-releasable buffers may not be fully usable for these purposes (see Section 1).

Second, while cyclical systemic risk is an important driver of potential losses, shocks with a sizeable impact on a substantial portion of banks can occur independently from the phase of the financial and economic cycle. As mentioned previously, the pandemic – while not captured in the chart below – clearly illustrates this point, although the extraordinary support measures prevented widespread loss materialisation. Overall, this speaks in favour of starting to build the buffer at an earlier stage of the cycle, so as to maximise the probability of having sufficient releasable capital available when a (potentially disruptive) shock occurs. Of course, the analysis in Chart 3 is only illustrative and needs to be complemented with further work on the precise calibration of positive neutral rates. For instance, stress test-based approaches, model-based assessments and further analysis of historical losses can be used to further inform the calibration of the rates.

Chart 3

Return on RWA in banking crises, depending on the level of cyclical systemic risk

Sources: SNL Financial, crisis data from Lo Duca et al. (2017), systemic risk indicator (SRI) from Lang et al. (2019).

Notes: The charts show distributional characteristics for the return on risk-weighted assets (RWA) around systemic banking sector crises, using annual data for a sample of 232 banks from 14 banking union countries covering the period from 2005 to 2019. Observations are taken from the period from three years before to five years after the respective banking sector crisis started. The sample is split into banks from countries where, in the years before a crisis, the SRI developed by Lang et al.(2019) was above (left panel) or below (right panel) the optimal signalling threshold for a forthcoming crisis.

Besides providing resilience against different types of shocks, a positive neutral rate also allows for a more gradual build-up of CCyB rates in the upward phase of the cycle. As illustrated in Chart 3, CCyB rates at the peak of the cycle need to be substantial if they are to be effective as a shock absorber. Starting the build-up at an early stage of the cycle would make sense given the observation that there are limits to the amount of capital that can be accumulated within a short period and without inducing undesired side effects. It would also address concerns about measurement uncertainty with respect to cyclical risk signals as well as transmission and implementation lags associated with macroprudential policymaking.In addition, gradual increases in capital requirements in a standard risk environment with favourable macro-financial conditions are unlikely to have a notable impact on credit supply, since banks are usually able to generate capital (for instance via retained earnings) and do not need to constrain the quantity of credit to meet higher requirements.This also speaks in favour of rebuilding the buffer after a release as soon as conditions permit, although the precise schedule for rebuilding is likely to depend on the specific nature of the crisis as well as country-specific factors.Overall, building up capital buffers in normal times creates insurance at low cost against systemic risks that are inherently difficult to capture and can be very costly when they materialise.

Over the medium term, a more harmonised approach towards setting positive neutral rates across banking union countries would seem desirable, since it would enhance consistency and effective policymaking across these countries while allowing for sufficient national flexibility. Thus far, countries that have implemented a positive neutral rate have taken different approaches, resulting in varying positive neutral rates, while other countries have not yet taken any action.This appears natural in a period of transition when authorities are looking to find the right buffer rate. In addition, as already mentioned, some divergence across countries can also be justified by structural differences between the respective economies. However, over the medium term, some harmonisation across banking union countries would be desirable so as to ensure the effective and consistent use of the CCyB across countries as well as a level playing field. Issues that would be considered by a more harmonised approach include, for example, the calibration of the positive neutral rate, the conditions for the build-up, release and subsequent restoration of the buffer, and the interaction of the positive neutral rate with other capital buffer requirements. In addition, the approach would need to leave sufficient flexibility and policy space for addressing cross-country heterogeneity and time-varying fluctuations in cyclical systemic risk. Finally, in the current environment, the implementation may need to be gradual and allow for a sufficiently long transition period, depending on country-specific conditions.

First, please LoginComment After ~